Rock ‘n’ roll as we know it today is usually attributed to white artists and acts. With many big names like The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Elvis Presley who made their careers through this style of music, it would be easy to believe that rock ‘n’ roll music is a genre by whites, for whites. The history of rock ‘n’ roll is deep, marred by a dishonest origin and is hardly told.

The term “rock ‘n’ roll” was coined in 1951 by a Cleveland radio DJ named Alan Freed. Freed worked for a major radio station during a time when large stations were known to only play music by white artists to cater to their white audience members.

He defied this industry standard and played R&B records — a style of music that was dominated by black artists — on his radio show. To avoid the stigma attached to R&B and to gain white acceptance of black artistry, he needed a new term to label the style of music he played.

Freed’s answer came from the 1951 single “Sixty Minute Man,” by all-black group Billy Ward and his Dominoes. The lyrics “I rock ‘em, roll ‘em all night long,” inspired the term “rock ‘n’ roll.”

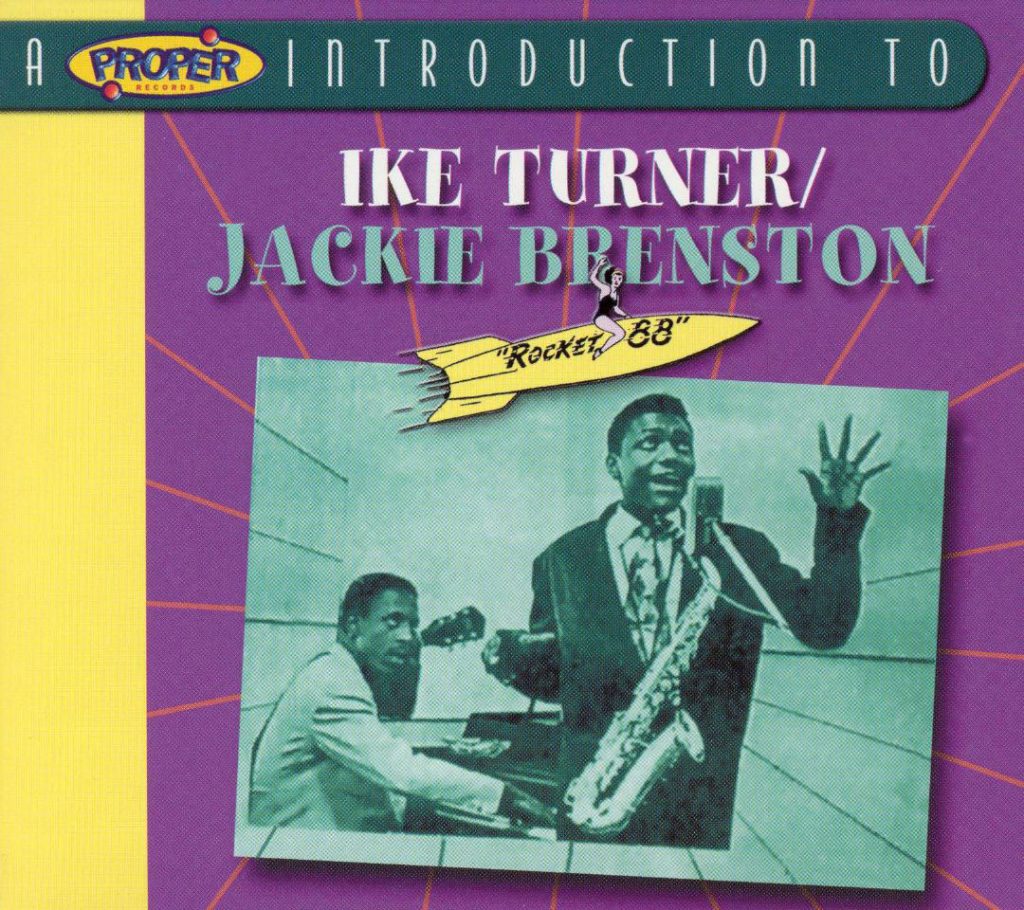

Later that year, Jackie Brenston and Ike Turner released the song “Rocket 88.” With its distorted electric guitar and heavy backbeat, “Rocket 88” is often cited as the first rock ‘n’ roll record, according to an article published on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s website.

However, the history of rock ‘n’ roll goes back even further.

The genre evolved from the African American musical styles of gospel, blues, jazz and R&B. These styles were derived from the call-and-response vocal patterns of the early African slaves. Elements of rock ‘n’ roll can be found in nearly every jazz, blues and R&B song — even those dating back to the 1920s.

By the 1940s, R&B had established itself as a black genre, with artists like Fats Domino and Arthur Crudup leading the way. Soon after, record labels took notice of the “new” style of music and wanted to capitalize on it. But they did not want the authentic, original black artists; they wanted marketable artists, ones who could be televised and proudly promoted: white artists.

Sam Phillips, a record producer and the founder of Sun Records, was at the forefront of the race to find white artists who could sound like black artists. According to The New Yorker, there is a story — albeit a disputed one — about comments Phillips made about finding black-sounding white artists. He allegedly said: “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.” Regardless of whether he said those words verbatim or even said them at all, there is truth to the sentiment.

Immediately, popular white pop artists were urged by their record labels to do covers of new rock ‘n’ roll records, without permission from the original artists, according to documentary miniseries “The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll.” White artist Pat Boone did covers of songs like Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame,” and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti.” Additionally, Bill Haley and the Saddlemen recorded a cover of Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88.” These covers all reached No. 1 on the Billboard Pop charts, since rock ‘n’ roll was not a category at the time.

Then came along Elvis Presley, a young, talented musician, who became known as the supposed “king of rock ‘n’ roll.” Presley grew up in a poor neighborhood in Memphis, Tennessee and intermixed with the black population for most of his life. He was heavily influenced by black culture and black music.

At the age of 18, he was signed to Phillips’ Sun Records after their first meeting in 1953. He had all the qualities that Phillips was looking for — as the Memphis Press-Scimitar put it, “He has a white voice [and] sings with a Negro rhythm.” The following year, he was covering R&B songs including “That’s All Right,” by Arthur Crudrup and “Hound Dog,” by Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. According to The New Yorker, these covers sold more copies and charted higher than the original versions sung by black artists.

Quickly, white artists stealing black artists’ music became the norm, to the point that the average white consumer believed that the covers they heard were the original sounds of rock ‘n’ roll. Many of the white artists never gave official recognition to the original performers, nor did they pay out royalties. It is true that most of these actions were spearheaded by the record labels, but most artists did not do anything to counter the practices.

Today, there is an appreciation for the talent and artistry of many black rock ’n’ roll pioneers like B.B. King, Chuck Berry and later greats, such as Jimi Hendrix and Prince. But the story of how rock ‘n’ roll got to where it is today is not always told. Its shady history is deliberately hidden, and oftentimes, too much credit is attributed to the wrong artists.