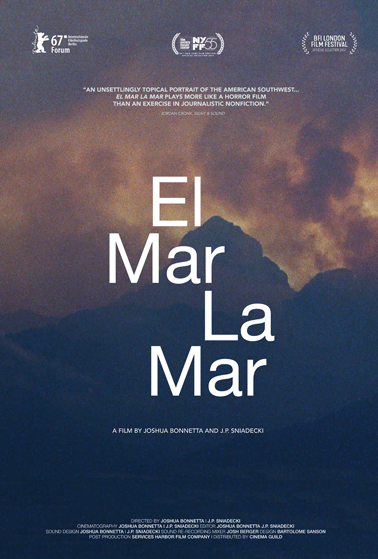

When you take on a project dealing with immigration, especially something as sensitive as the U.S.-Mexico border, one cannot discount how race plays into it. This was my biggest concern after viewing “El Mar La Mar” by Joshua Bonnetta and J.P. Sniadecki. This was Harpur Cinema’s first screening of the semester, introduced by Chantal Rodais, a lecturer in the cinema department, as a film “that challenges borders.” Tomonari Nishikawa, an associate professor of cinema, added that it is a film less focused on how the shots are exposed and more focused on its structure. Further, the film was introduced by Bonnetta and was followed by a Q&A with him.

Shot on 16mm film, the movie is split into three parts. Due to nature of the medium, how the shot is exposed and the film stock used is usually a quality that is appreciated. As a whole, the film seems to makes an effort of almost completely separating audio from video. Most scenes consist of long, static shots of the Sonoran desert followed by a dark screen with audio of interviews playing over it. Because there is very little to no sync sound — which is when someone is talking on screen and you hear them at the same time — it becomes very important when something is audible while we are also viewing something. One of the most striking shots early on in the film is striking for how difficult it is to initially decipher. Shot on a telephoto lens, it is clear we are in a car driving past shrubbery, but the screen is interrupted by multiple vertical lines cutting across the frame, almost in the fashion of zoetropes. It slowly becomes clearer that we are viewing beyond the border wall and that the lines are the rungs of the fence. Immediately we are given this imagery of being trapped and a feeling of surveillance, which becomes a theme throughout the film. This is contrasted with shots of the vast and seemingly empty desert, allowing the audience to understand how daunting of a trip traveling through the border is.

One of the earliest monologues we get is by a woman who lives by the border. She describes how late one night, a man came knocking at her door, begging to be let out of the cold. Another man relates escaping a patrol in the desert. He describes that you can easily get lost, not so much because of visibility, but because it’s so plain and far that you don’t know where you are or where to go. The film goes on telling of what gets left behind in the desert and the emotions experienced when finding objects like toys or diapers. A shot toward the middle stands out to me due to the nature of surveillance it evokes: a cone of light from a flashlight shines into the shrubs of the desert as the cameramen drive by. At this point, the film seems to position the audience in a manner similar to U.S. Border Patrol, offering that the viewers may be part of the problem.

The Q&A started with a question about the title, which revealed it was a reference to the Rafael Alberti poem. This came about after Bonnetta and Sniadecki both agreed that the cacophony of sound present in the desert at night reminded them of a sea. After finding the poem, they agreed it fit this theme of being in one place and longing for another. Another audience member wondered why most of the monologues of people interviewed were paired with a black screen, to which Bonnetta replied that this actually wasn’t the case. He claimed it was actually footage of a storm, and as the film progresses, so does the storm over the desert. In the opinion of this reviewer, this distinction is quite moot as it is impossible to tell due to the low exposure of the film, but I do agree with Bonnetta’s point about it. Having such an abstracted view “allows the stories to speak in a more democratic form.”

I then asked Bonnetta about how interviewees were chosen and whether the directors considered how interviewees’ backgrounds could’ve played into their responses. This came about after I realized a majority of those interviewed seemed to be American citizens who happened upon cases of Latinx pain. This is not to say that immigrants and those who have been in the thick of the desert weren’t also interviewed, but I often wondered if maybe some context was considered in terms of bias and race. Bonnetta was not very receptive to the question and mostly stated they interviewed anyone who would talk to them — that they were “mostly accidental.” In terms of the monologues recorded from the immigrants, the translated subtitles from Spanish to English were questioned by an audience member. Bonnetta confided that during filming, Sniadecki, who is “kinda like a polyglot,” was learning Spanish, so they decided to translate it themselves. It wasn’t until presenting it at the Berlin International Film Festival that they realized the translation was very wrong. Since then, it’s gotten multiple edits with the help of translators, according to Bonnetta.

This gets at my main issue with the film. When speaking on how it came about, Bonnetta mentioned that they were actually there to shoot another film, but being near the Sonoran desert made them want to record everything, and thus this film came out sort of by accident. And that’s how it feels sometimes. Not to downplay the thought put into the film, but the approach feels like the point of view of a tourist, someone who happened upon this politically charged area and collected bits from it. There isn’t so much a political backbone or anything ultimately being said about this strife other than highlighting it and trying to characterize its nature.

Honestly, I’m kind of over white directors, in a sense, benefitting off human suffering, even if it isn’t explicit in this case. In a film highlighting the tensions between Latin American immigrants and U.S. citizens at the Sonoran border, it’s almost a glaring hole how sanitized the topic of race was presented.