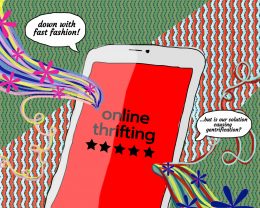

It’s undeniable — the secondhand clothing movement, brewing since the mid-2010s, has become mainstream and is well on its way to making waves. Though fast-fashion giants like Fashion Nova, SHEIN and Forever 21 haven’t been toppled from their thrones (yet), the practice of buying used clothes, formerly associated with a low-income lifestyle, is now considered quite chic, with the “recommerce” industry at large consistently outperforming the overall retail industry for the past six years. In recent years, the widespread diffusion of this already-popular sentiment among the younger generation has been further catalyzed by social media. Buying secondhand not only offers the opportunity to get one-of-a-kind pieces for low prices, but is also an ethical alternative to “firsthand” clothes-shopping in an era where corporate practices are placed under a microscope. It should be noted that the rationale behind monitoring corporations is reasonably strong, for its findings thus far have been pretty disheartening. In the fashion industry, corporations seek to take advantage of the toothless labor laws found most commonly in developing nations. Here, the companies can cut both ends of the stick, forcing workers to perform skillfully despite their abysmal work environment and excessive hours in dangerous conditions with mandatory overtime — all for pay that’s so low it’s often not even a living wage. From time to time, the culmination of these circumstances has erupted in a way that garners media attention, such as the collapse of a building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which killed over 1,100 workers and injured another 2,000. In the wake of such devastations, many people have started to rethink the ethicality of the corporations they help sustain if they are financially able to.

With the rise of thrift shopping comes the rise of digital secondhand retailers. Especially given the pandemic and its effect on the economy, secondhand clothing sites have become all the rage, among the most popular being Depop. The UK company, founded in 2011, changed the game by bringing buyers and sellers together. Its Instagram-esque interface creates a personal feel, emphasizing Depop users and tailoring an aesthetically mindful shopping experience to cultivate a creative, vibrant community. These are just a few explanations for Depop’s undeniable success, amassing 15 million users in 147 countries, around 90 percent of whom hail from Generation Z. While Depop sellers retail a diverse range of merchandise, many users have a bone to pick with one particular type of Depop seller.

This seller is more specifically a reseller — they hit the thrift with the intention of re-listing their finds at marked-up prices to make a profit. Oftentimes, this notion of “The Depop Seller” evokes a stereotype depicting something like this: a conventionally attractive, slim, teenage girl, a businesswoman-in-the-making, simultaneously managing sales and cultivating her brand. She’s the epitome of cool, today’s youth’s equivalent to our 2014 Tumblr-era Acacia Brinley. Yet, as campy as this image may be, sellers like these are the ones Depop critics take issue with, claiming that this buy-and-resell business model leads to the gentrification of thrift stores.

Though the term has no clear-cut definition, “gentrification” can generally be defined as a process in which an influx of middle and upper-class peoples move into a low-class neighborhood, then “renovate and rebuild” existing residences and businesses. The term was first coined in the “Radical ’60s” by sociologist Ruth Glass, who observed that while gentrification may “‘uplift’ previously run-down” neighborhoods, this often comes at the expense of undermining established local character, culture and history. Locals, unable to afford the elevated cost of living, may be displaced from their homes. At best, it’s misguided and paternalistic — at worst, since research correlates gentrification with racial inequality, it’s yet another manifestation of white superiority. Many view the rising prices at tried-and-true thrift classics like the Salvation Army and Goodwill as a form of gentrification, especially when stores are located in poorer areas, and attribute the cause of this to the observable surge in Depop clothing resellers.

However valid this concern may be in theory, it is not quite valid in practice. In the United States, only 20 percent — a relatively small portion — of used clothing winds up in secondhand stores. The remainder of this clothing has one of three fates: some is carted off to developing countries and sold to locals at discounted prices, another portion is recycled in textile factories and the rest winds up in landfills. According to the EPA, the last category is the vast majority, as 85 percent, or 12 million tons, of thrift store donations are shipped to landfills annually, accounting for 7 percent of the nation’s landfill waste.

Thus, it’s evident that thrift store giants, like Goodwill, have no shortage of inventory — in fact, the reality is quite the opposite. Beyond this, said inventory consists of donations. Thus, they can acquire inventory at virtually no cost to the company. These facts undermine the basic principle of the law of supply and demand within their own context, and by extension, any justifiable cause for the raised prices. In other words, even when demand increases, if the supply is so enormous it’s virtually impossible to fully deplete, and acquiring this supply costs relatively nothing, the price doesn’t actually need to increase.

Blaming Depop resellers as being the root cause of the issue is thus misguided. In actuality, it is corporate greed, not teenagers, that serves as the driving force behind increased thrift prices. As far as Depop resellers go, some price markup is understandable — it takes time to curate items, take photos for item listings and respond to potential buyers. Plus, non-sellers may not consider the fact that sellers pay both Depop- and PayPal-based fees, which can add up depending on the item. That being said, it’s important to maintain one’s integrity — reselling $4 Hello Kitty T-shirts from the children’s section for ten times the price and labeling it as a “Vintage #Y2K Baby Tee” is comically distasteful, and a rip-off unsuspecting younger buyers will almost always fall for.

May Braaten is a freshman majoring in philosophy, politics and law.