On Sept. 29, NASA astronaut Jeanette Epps spoke at the Innovative Technologies Complex about the difficulties of wearing a 300-pound space suit and training to operate robot arms. What she didn’t mention was her gender.

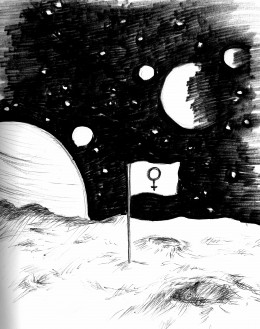

Although attendees and sponsors praised Epps as an inspiration to young girls, her accomplishments are impressive regardless. The notion that competent women are outliers is the final frontier we must overcome in breaking through the glass ceiling women face entering the STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields.

Thankfully, the institutional constraints on women wishing to pursue STEM careers are dissolving. That Epps and other female astronauts are able to reach their positions based on merit reflects this shift. Tech companies like Google actively recruit women and willfully disclose their employment demographics, acknowledging that a workforce dominated by men is undesirable. As we can see from the retroactive outcry over chemist Rosalind Franklin’s lack of Nobel Prize recognition for her work in the discovery of DNA, we’ve come a long way from the time when female scientists weren’t given credit for their discoveries.

While structural constraints may have deteriorated, women still aren’t entering STEM careers at the same rate as their male counterparts. Women hold fewer than 25 percent of STEM jobs. At BU, it’s common to walk into Watson lectures and see only a handful of women sitting in the seats.

Though the environment is beginning to change, some women simply haven’t been encouraged to pursue STEM-related careers. From a young age, girls are socialized into believing they are not biologically suited to excel in STEM. Popular wisdom holds that women and men are hard-wired differently. Exaggerations of the findings showing the subtle differences in brain structure persist: Women are thought to be biologically suited to verbal proficiency and memorization while men are suited toward compartmentalized, spatial reasoning. Reliance on outdated research ignores advances in understanding of the human brain. Neuroscientists theorize that differences in brain behavior could be a result of socialization itself, as brain functions change in response to experience. So by teaching girls that their professional callings lie elsewhere, we may actually be causing them to perform poorly in math and science.

Even the way young girls are taught science is problematic. A viral photo of the Carnegie Science Center’s fall programs for Scouts demonstrates the persistence of gendered norms in education. Boy Scouts are offered a variety of program options in chemistry, robotics, biology and astronomy. Girl Scouts are offered “Science with a Sparkle.” Carnegie’s defenders argue that pink-washing science sparks an interest among young girls who are naturally more attracted to sparkles than chemistry kits. Sparkles aren’t inherently inferior, but the absence of choice limits girls. The lack of choice reveals the root of the problem: The continued prevalence of the false idea that girls are biologically suited to a limited way of thinking.

At BU, students are breaking those traditional barriers. Rebecca Tanzer, a junior majoring in mechanical engineering, helped develop a satellite at NASA. When she was there this summer, she sometimes realized that she was the only woman in the room. And in Alpha Omega Epsilon, the professional engineering sorority, Mandy Boltax, a senior double-majoring in computer science and English, worked on the design of eBay’s website and developed new software at Microsoft.

Successful women like Jeanette Epps may be an inspiration to young girls interested in the STEM field. Girls surrounded by such role models are shown to be more likely to pursue STEM careers. But in order for more women to enter STEM, we need more than role models. Encouragement must come through educational reform, from the earliest period of socialization to the college level.

As Epps has proven, the sky is hardly the limit.