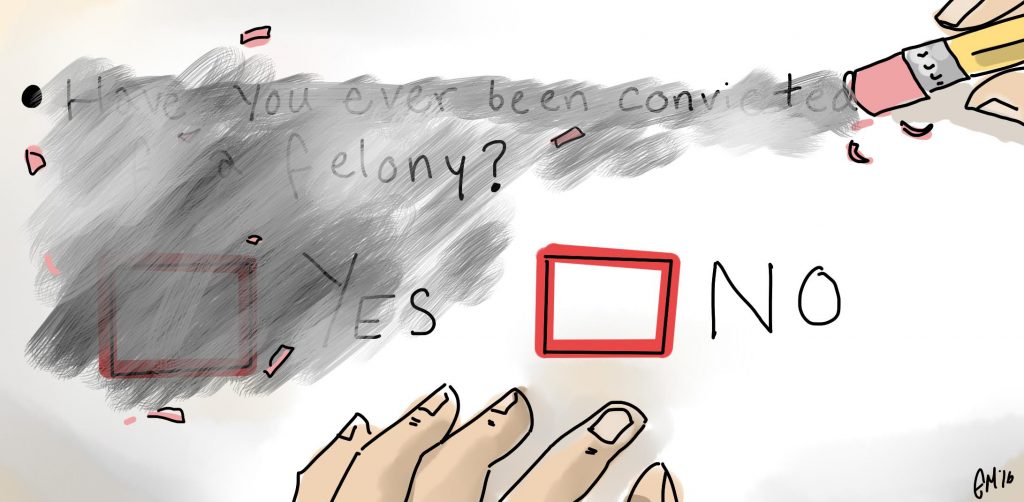

Last week, the SUNY Board of Trustees voted to “Ban the Box,” meaning public colleges and universities in New York state will no longer require applicants to declare felony convictions prior to admission. This change will allow applicants with documented criminal offenses to be considered not in light of their mistakes, but based on their merit.

The United States has an incarceration rate far past all other developed countries; although home to only about 4.4 percent of the world’s population, our nation contains over 20 percent of the world’s prison population. Societal flaws stemming from of legislators, employers, educators and law enforcement officials create cycles of poverty and disadvantage that often lead to prison and are almost impossible to escape.

Even nonviolent drug convictions can follow one for the rest of his or her life, keeping one from education and employment. This is not to say that all crimes should be forgiven, but once someone serves the time to which they were sentenced, that person should be able to integrate back into society. And once those convicted have served time, they definitely should not be restricted from opportunities that are open to the rest of us.

By banning the box, SUNY is recognizing that these flaws exist and working toward creating a system that will not hold prospective students back based on them. However, it is important to address the fact that this action is only one stitch on a gash of a problem.

Banning the box only applies to the application process itself; once accepted, students can be asked about their criminal history when applying for financial aid, student housing, internships, study abroad programs or any other University services. Although their admission cannot be revoked, they can be denied any of these aforementioned services based on past convictions.

Banning the box has also shown to have the unintended consequence of replacing one form of discrimination with another. A study by the University of Michigan found that some employers who embraced banning the box were less likely to hire nonwhite employees when applicants were not asked to report felony charges, shining a light on unfounded assumptions about race and incarceration.

The move by SUNY attempts to remove the barriers for people with felony convictions to enter the education system, while not touching the ones within or beyond it. It is still difficult for those with felony convictions to find employment outside of school. This begs the question: What good is equipping people with degrees if they cannot use them?

Indeed, it is no simple task to break the cycles of poverty, disadvantage and discrimination. Hopefully, employment discrimination will also change as our society becomes more cognizant of flaws in the penal system. Despite the challenges they will still be sure to face, these applicants are at least now granted the opportunity to get a college degree — a step which will hopefully give some a boost into a better life.

Moving forward, the SUNY system must be deliberate in monitoring the successes and failures of this new initiative. If it were enacted truly with the intention to improve the lives of those who are otherwise disadvantaged, then they must examine the impact it is having and accordingly work to address the barriers and flaws the exist beyond the point of entry.