Every day, about 22 U.S. veterans commit suicide, which does not include the number of veterans slowly dying from drug and alcohol addiction, according to Frank Romeo, activist and Vietnam War veteran. As part of his project, “Walk With Frank,” Romeo made a stop in Binghamton while walking across the state to raise awareness for veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

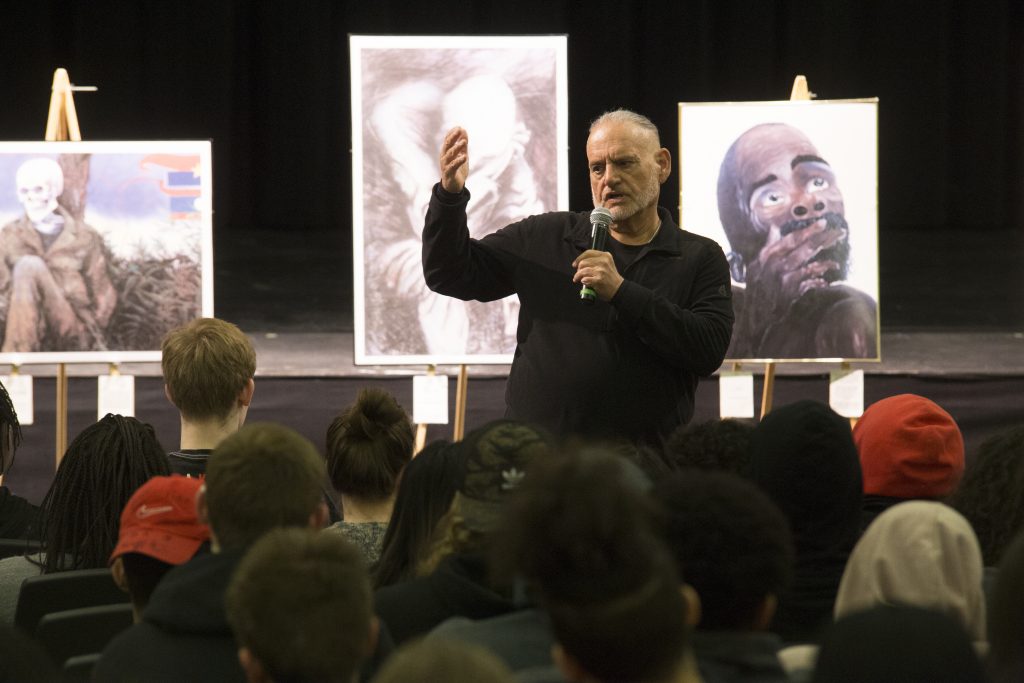

Romeo, 70, is one the oldest living Vietnam War veterans diagnosed with PTSD and has spent the last 30 years using his trauma as a tool to teach people about the reality of war and the effects it has on U.S. veterans through art and a reality-based teaching curriculum he developed. Romeo started “Walk With Frank” in Buffalo, New York, and is heading toward Bay Shore, New York, stopping along the way to stay in homeless veterans’ shelters and share veteran experiences with young people. While in Binghamton, Romeo spoke at Binghamton High School.

While speaking to students, Romeo outlined his experience serving in the U.S. Army. He enlisted in 1968 and was a member of an elite unit called the 199th Light Infantry Brigade, which was engaged in covert missions in Cambodia when Romeo was separated from his unit, taken prisoner and shot multiple times by enemy troops. When he was found and rescued, he spent a year in the hospital, undergoing multiple operations until he was eventually released.

But when Romeo was discharged, he wasn’t diagnosed with PTSD because it didn’t exist at the time. According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the term PTSD was not medically named until 1980. As a result, he was initially diagnosed with multiple anxiety disorders, but he said that his physical disabilities, addiction issues and lack of real understanding of the causes of his mental disabilities heightened his trauma.

“I had a very difficult time dealing with my PTSD, my anxieties, sleepless nights, nightmares,” Romeo said. “I got into drug and alcohol abuse that lasted for decades — I started showing signs of what we know now as PTSD. It wasn’t known as that, they didn’t know what it was, they diagnosed me with everything from [Vietnam Syndrome], to depressive neurosis, shell-shock, any number of things. It would only be 30 years later that they actually came to terms with the idea of it being PTSD.”

In an effort to deal with his undiagnosed PTSD, Romeo began creating art. He said once art became a part of his own journey with PTSD, he was inspired to seek out others who cope in the same way, and he has spent years collecting hundreds of art pieces created by veterans trying to deal with the realities and traumas of war. At each stop along his walk, Romeo’s team goes ahead of him and sets up the works of art to provide people with a visual for the difficulties people with PTSD encounter on a daily basis.

“I was able to funnel my PTSD into creating artwork, and then collecting artwork from other veterans,” Romeo said. “I searched out artwork from other veterans, and then I realized we were documenting the emotional history of our country through art and the story of PTSD from its inception, from the Vietnam era, from the battlefield right up into today. This artwork told a story of men suffering, and each painting had its own story behind it and then you put those stories together and you have an entire book, you have volumes that speak on the American soldier and a period in history and our contributions to society today.”

In addition to sharing the story of the American soldier through art, Romeo also aims to convey veteran experiences in the classroom. He has designed a specific curriculum, “The Experience of the American Soldier,” for 11th-grade history classes. Teachers can integrate the program into the preexisting curriculum. Romeo said he hopes to draw the focus of history classes away from the actual battles and toward the soldier and the experiences that individuals face both during and after the battles.

“What we have is not a new curriculum but one that is woven into the mainstream American history, social studies and government classes, so all 11th graders in New York state can get into this curriculum if they’re in any of those classes,” Romeo said. “We’ve designed a program that spends less time studying the battle and a little time studying the soldier that’s in the battle. You still learn about the battle, only through soldiers, now you’re learning who is a soldier and who is a veteran.”

While traveling through Binghamton, Romeo was joined by his nephew, Nicholas Zecca, an undeclared freshman at Binghamton University. Zecca said it has been touching to watch “Walk With Frank” come together.

“In 2014, he went back to Vietnam to see and visit the places he fought and that was really good for him and he’s been doing his art of war exhibit for 30 years,” Zecca said. “So I’ve seen that and it’s really moving to see because he sets up a lot of his art and relevant things that were going on in the late ’60s when he was fighting there. He shares some of his personal stories as well through the things that he puts out and the things that he talks about.”

Romeo said he considers it to be his purpose in life to provide people with an example of someone dealing with similar trauma to them and give people an opportunity to explore that trauma and learn from their past. While answering questions from students, he said the added stress and pressure of civilian attitudes toward veterans made dealing with his trauma even harder, and illustrated the importance of giving people the tools and information necessary to have productive conversations about trauma so that no one has to suffer on their own.

“Finally, when PTSD was recognized for us, we began to understand it’s a basic human emotion, it’s in us all,” Romeo said. “We all have the propensity to be traumatized and then react in that way. And we just keep sending out children off to war, mentally unprepared.”