A lawsuit filed against SUNY and several high-level Binghamton University administrators is moving forward.

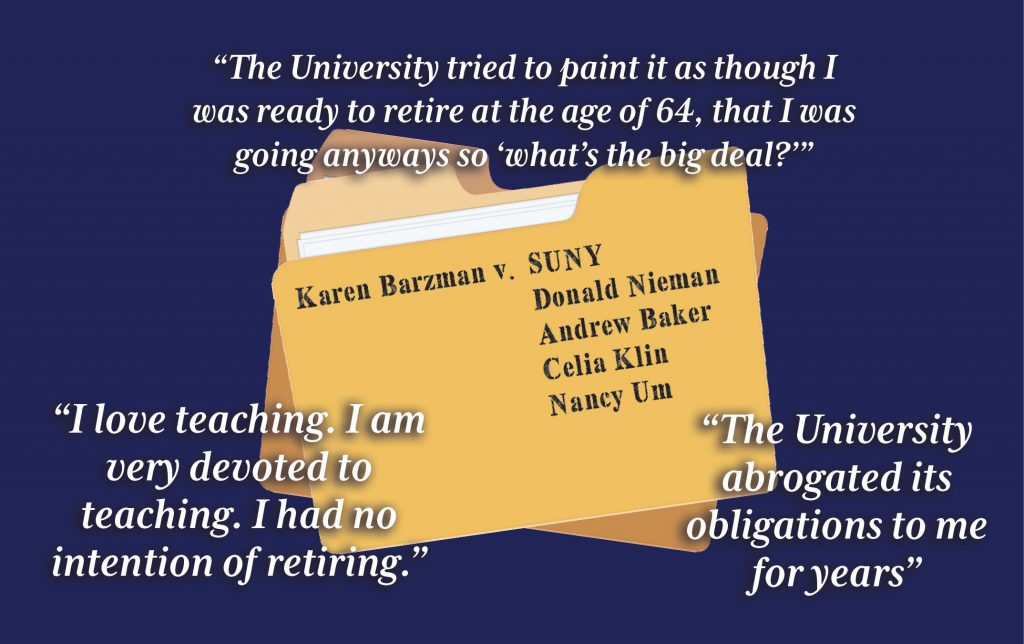

In recently filed court documents, a case filed by Karen Barzman, a former professor of art history at BU, was allowed to proceed after a motion to dismiss was denied. The action accuses SUNY and codefendants Donald Nieman, a former provost and current professor of history, Celia Klin, the current dean of Harpur College, Andrew Baker, the Title IX coordinator, and Nancy Um, a former dean for faculty development and inclusion, of sex-based discrimination and retaliation under Title IX and the New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL).

The concerns began with Barzman’s relationship with John Tagg, a SUNY distinguished professor in the art history department, which was “tumultuous and involved physically violent and emotionally abusive conduct by Tagg.” After Tagg arranged for Barzman’s hiring at BU, he began abusing her at work by treating her in a demeaning manner and encouraging colleagues to mirror his actions, according to court documents. After the relationship ended in 2005, Barzman alleges that Tagg encouraged department allies and junior employees to mistreat her by ignoring and criticizing her at events, cutting off communication regarding professional developments and giving her worse teaching assignments.

In 2021, Barzman accepted a University arrangement to receive one year’s salary and complete supervision of her remaining doctoral students in exchange for severance of her relationship with BU. She characterized the agreement as compulsory.

“They forced me to sign an agreement that made it look like I was willingly retiring,” Barzman said. “[They] kept calling it an ‘early retirement agreement.’”

In 2021, along with all faculty, staff, graduate assistants (GAs) and teaching assistants (TAs), Barzman had to complete a Title IX training module, in compliance with “state law and University policy.” According to the module, “supervisors and managers are held to a higher standard,” and are required to report any cases of harassment or violence communicated to them, observed or that they should have “reasonably known about.”

After completing the module, Barzman contacted Klin, the then-acting dean of Harpur College. She described how Klin was initially sympathetic, promising to speak to higher administration about transferring her away from the abuse within the art history department, but then ultimately denied her request after speaking to the provost, Nieman.

“The University abrogated its responsibilities to me for years,” Barzman said.

Pipe Dream requested, but was unable, to receive a comment from BU administration.

Barzman recalled confiding in many faculty members above her in rank — including chairs of other academic departments and administrators that answer only to the University president. Ultimately, she said that “nobody fulfilled their obligations under Title IX,” which mandates that administrators take “immediate steps” once made aware of an incident, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network — an anti-sexual violence nonprofit.

Barzman, now a scholar in residence at the Newberry Library in Chicago and an adjunct lecturer at DePaul University, described the impact on her professional life.

“I was a fully tenured, full professor with doctoral students and an international reputation as a scholar,” Barzman said. “Now I’m an adjunct instructor. [I’m] grateful to have this job because it’s something.”

In their motion to dismiss Barzman’s lawsuit, the defendants listed five points — the first argued that employees were not entitled to sue under Title IX, the second mentioned the statute of limitations, the third said that an “actionable sex-based Title IX harassment claim” was not stated, the fourth concerned claims against individual defendants and the fifth contended that the court should not exercise jurisdiction over NYSHRL claims. Every motion was denied by the court.

Barzman remembered some colleagues as “uncomfortable” when hearing her story, which she argued impeded receiving justice and protection from administrators. Kara Chadwell, the president of Domestic and Oppressive Violence Education (DOVE) — an organization dedicated to educating students and the larger community about forms of domestic abuse — and a senior double-majoring in human development and philosophy, politics and law, explained the impact of not communicating about sensitive issues on victims of domestic violence.

“I think for the most part, our society has a culture of isolation, especially when it comes to a victim,” Chadwell said. “Starting from a young age, when you’re not having open and honest conversations about difficult topics like this, [people] become accustomed to not talking about things and then it’s uncomfortable, and then they don’t want to, and then when someone comes to them with an issue, they don’t know what to do.”

Victoria Barics, the treasurer of DOVE and a senior double-majoring in psychology and philosophy, politics and law, emphasized the importance of listening to survivors with understanding.

“I think that it’s very important that when somebody opens up about something like that, they get to have someone listen with a very empathetic ear,” Barics said. “As far as [Barzman’s] experience, and just in general, just having all these people [react] in not the most supportive way can have that negative impact.”

Editor’s note (5/3/23): A previous version of this article stated that Barzman met with Klin in 2019. This article has been fixed for inaccuracies.