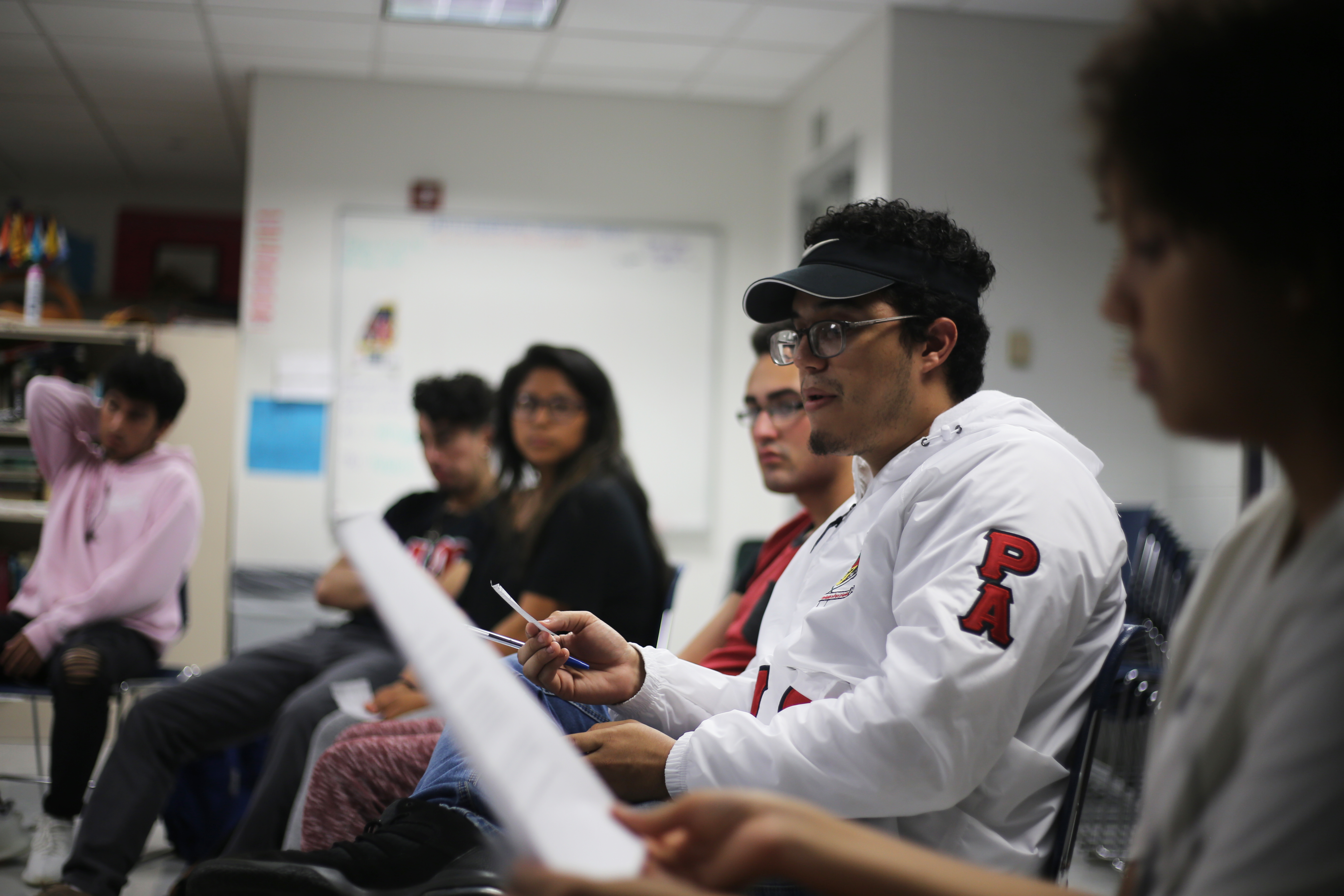

In a room in the University Union, a group of students from the Latin American Student Union (LASU) scribbled down responses about their racial and ethnic identities on copies of the 2000 U.S. census.

On Monday evening, LASU discussed the importance of the U.S. federal census in communities of color, the consistent underrepresentation of the Latinx community and the potentially limiting categories they have to check off. Students also shared their personal thoughts and feelings on the upcoming 2020 federal census.

Each attendee was given a sample of the 2000 U.S. census to fill out. When the censuses were returned, Alexandra Gonzalez, historian of LASU and a sophomore majoring in human development, surveyed the room for reactions.

The census asked if each person was Spanish, Hispanic or Latino, and beyond that, whether they were Mexican American, Cuban American or of a different Hispanic or Latino heritage, designated by “other.” The following question on the census asked students to list their race, checking one or more from “Black,” “White” and “American Indian.”

Jahmal Ojeda, vice president of LASU and a junior majoring in political science, said he thinks the race classifications are too divisive.

“They shouldn’t break up the categories,” Ojeda said. “It makes us feel like we’re not just one connected community.”

“These categories are a way of controlling people,” Garcia said. “The census was made to manipulate the masses and create policies that intentionally discriminate against people of color.”

The term Latinx is often used by people of color, as it is inclusive of people from a diverse set of racial and national Latin American heritage. Garcia spoke about her experience as an immigrant using the term.

“For immigrants, we identify ourselves more by our nationality or our ethnicity more so than our race, like I’m Colombian,” Garcia said. “In the United States, we use ethnicity because it’s a more unified thing.”

The U.S. census is used to allocate resources to certain communities. Therefore, it’s vital for communities to fill out the census in order to receive their fair share of governmental support. Historically, federal aid to communities of color has been lacking.

Garcia also discussed the threat to services that target Latinx-specific health risks as a result of misidentification. Without accurate census records, these benefits could be jeopardized.

“They use the census for health records,” Garcia said. “When you misidentify, they cut down on preventative measures that would help people in your community. Because a chunk of you chose to misidentify, you put your community at risk.”

The students also discussed the classifications themselves, specifically the use of the term “Hispanic.” While some students felt the term carried an undertone of colonization, Aylin Gonzalez, a senior majoring in English, said she identifies as Hispanic as it most accurately depicts her race.

“Although I understand that being Hispanic is not necessarily a race, I don’t see another race that aligns with who I am,” Gonzalez said.

Racism within the Latinx community was highlighted as a big issue that could lead to misidentification. Because of the complicated colonial past of Latin America, the African and Native American aspects of people’s ancestries are often brushed aside or purposely neglected.

“As Dominicans, it is instilled in us that the whiter you are and if you can trace your ancestry back to Europe, the better that makes you,” Gonzalez said. “My mom and my grandma were always like, ‘oh your grandfather had blue eyes, he was a French man, you’re not black.’ I was like, ‘first of all, I’ve seen my grandfather and he was none of these things.’”

Some students believed that there should be no check mark due to the inconsistent classifications they encountered on their censuses. For Garcia, she said the ambiguity of the categories led to more questions than answers.

“They’re always changing the categories,” Garcia said. “If they can’t make up their minds on how to categorize us, then how do we know which category we belong to?”