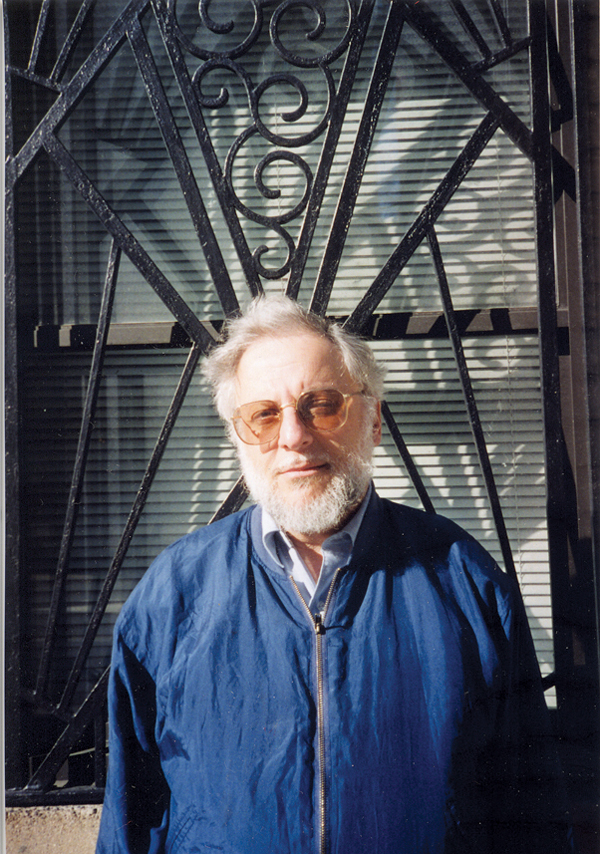

As protests that led to the departure of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak overtook that country’s capital earlier this month, Martin Bidney, a professor emeritus of English at Binghamton University, was on a farm just an hour from the heart of the movement in Cairo.

Bidney spent his time on an ecologically and environmentally sustainable farm, Sekem, located in a desert, where his main professional responsibility was coaching young teachers in English.

“I was teaching them an hour a day, but it quickly ramped up to four to five hours. They simply loved to learn,” Bidney said.

Bidney said the riots occurring in Cairo did not significantly affect his trip, but he and various people from the village where he stayed were stopped and questioned on expeditions into the city.

“We took an expedition to the Sakkara pyramid, and we were going to see more that day, but we were told the armies had closed them off,” Bidney said. “Other times we were stopped by soldiers on our trips to Cairo but our passage was not restricted.”

Although Bidney did not have Internet access, others living in the community had some access where they could check daily reports on the Cairo riots.

“I got to see the state of the country from an unusual perspective of local conditions, from a community that has been exceptionally well-governed,” Bidney said.

Bidney added that the students at the school were writing essays and talking about the riots in Cairo.

“We certainly discussed the changes as they were coming,” he said.

According to Bidney, all the students had similar hopes for progress, and Bidney said he did not hear any support for Mubarak.

He added that his location at the farm was secured when extra guards were posted at times of potential danger.

“We were kept very safe the entire time,” he said.

He was skeptical of the amount of change the riots would create.

“I began to have some doubt how radical changes would be despite the great insurgence,” Bidney said.

Bidney also added that the military handled the results in a relatively peaceful manner because they did not want to lose their secure economic position.

“The military had no particular motive to be anything other than orderly and peaceful in their management of the revolts,” Bidney said.

Bidney taught English and comparative literature at BU for 35 years and has been retired for six years and working on his own studies.

“I did not go there to study politics, but I did learn about it and how an environmentally stable farm in the desert can flourish and from the music, dancing and teaching, I profited culturally in many ways,” he said.

Some of the young activists who launched the uprising that toppled Mubarak said Monday they are skeptical about the military’s pledges to hand over power to a democratically elected government.

Their concerns came as British Prime Minister David Cameron arrived in Cairo to meet with top Egyptian officials and “make sure this really is a genuine transition” to civilian rule.

In a meeting with Western diplomats in Cairo, the activists appealed to the United States and Europe to change their policies toward governments in the Middle East.

Many activists in the 18 days of mass protests that toppled Mubarak on Feb. 11 complain that Western governments have long supported dictators who back their interests at the expense of local democracy.

“It is time that United States and Europe to revise and correct their policies in the region,” said Bahey al-Din Hassan, director of the human rights institute that hosted the meeting. “This has always been our message, and we hope it won’t fall on a deaf ears.”

— Information from The Associated Press was used in this report.