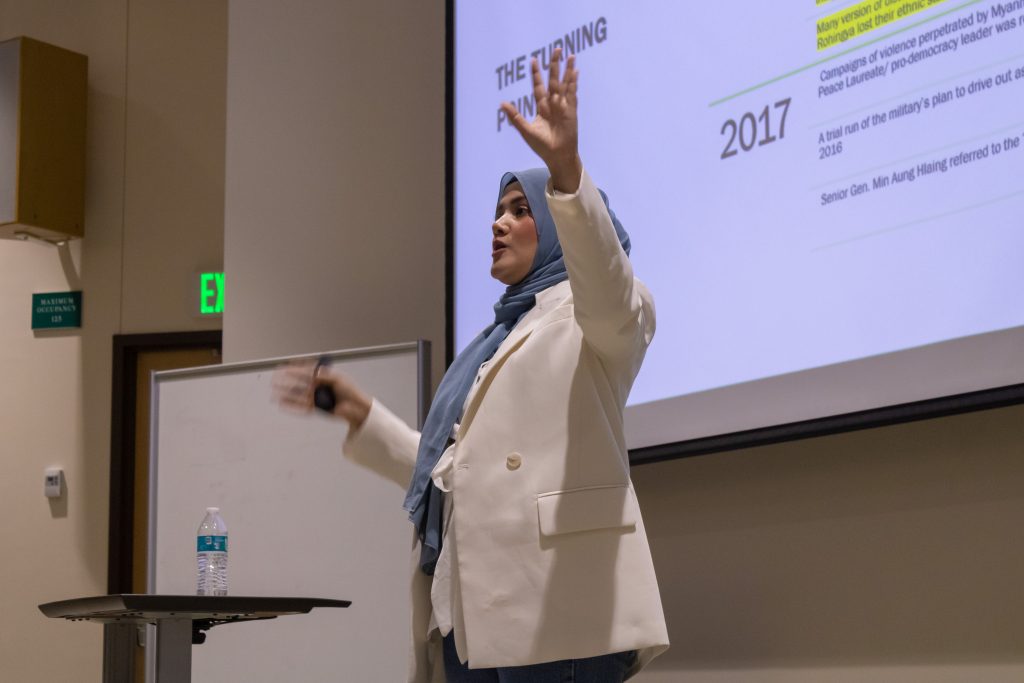

Yasmin Ullah, a Rohingya social justice activist, gave a presentation discussing the Rohingya genocide with Binghamton University students, faculty and community members on Tuesday.

Ullah has formally served as the president of the Rohingya Human Rights Network, a nonprofit group led by activists across Canada who bring public awareness to the Rohingya genocide. In 2021, she was named on The Gender Security Project’s “FemiList” of 100 women from the Global South working in fields such as foreign policy and peace-building. Ullah has also worked on projects to engage with Rohingya issues through an intersectional lens, both locally in Canada and on international levels.

Her presentation, titled “Rohingya Genocide: A Community’s Struggle for Agency,” focused on both the neoliberalization of Myanmar, the impact that state-sponsored atrocities had on the Rohingya population and ongoing efforts being made to rebuild their community.

The talk was held by the University’s Institute for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention (I-GMAP). Max Pensky, co-director of I-GMAP and professor of philosophy, said that I-GMAP focuses on bringing people together from across the world to work toward their mission of raising awareness and building effective prevention for mass atrocities.

“By bringing in practitioners we want to be able to break down barriers between the University and the rest of the world,” Pensky said. “So we encourage our students to come to our events and forums so they can educate themselves on these issues and the roles that activists play within our society.”

Ullah began by speaking about the history and influences that led the Burmese military and government to conduct a series of ongoing persecutions and killings of Muslim Rohingya people. As Ullah described, a group of Rohingya men were accused of the rape and murder of a Buddhist woman, resulting in Buddhist nationalists retaliating by killing Rohingya people, burning their homes and subjecting the community to brutality and discrimination.

This systematic violation of human rights by Myanmar’s military junta has forced thousands of Rohingya people to flee their country. Subsequently, it has compelled thousands to live as refugees, mainly in Bangladesh.

Ullah said discriminatory governmental practices have not only forced the Rohingya people out of their homes but also silenced their voices.

“There’s this [governmental] strategy to push Rohingya out of their land,” Ullah said. “They kill as many Rohingya [men] as possible, making the community live in fear. They force the women and children to watch and have them carry this trauma so they don’t dare come back to their homes.”

Anthony Ivanov, a second-year graduate student pursuing a Master of Public Administration with a certificate in genocide and mass atrocity prevention, discussed the gendered aspects of genocidal violence and how the crisis has impacted the well-being of the Rohingya population.

“I found out about this event through my class, called [Genocide & Mass Atrocity Prevention 503: Introduction to Nongovernmental Organizations], and after attending the presentation, it has left me to continue learning about mass atrocity prevention strategies within my future,” Ivanov said. “[Ullah’s] examples of how violence is enacted toward Rohingya populations in a way that causes women to carry so much of the emotional trauma and burden illustrate this point well, and I left with a greater understanding of the gendered aspects of genocidal violence.”

The Rohingya people have been subject to waves of violence, discrimination and persecution for decades, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. During her talk, Ullah aimed to provide insight into how the course of Rohingya history can change if people stand together as a community and spread awareness. Ullah emphasized that efforts should not look at the Rohingya population as victims but rather as survivors.

“Our work extends beyond what we are often portrayed as,” Ullah said. “We are not victims waiting for the world to rescue us. We have survived decades of genocidal processes because we work hard to survive.”

Julia Saltzman, a second-year graduate student also pursuing a Master of Public Administration with a certificate in genocide and mass atrocity prevention, echoed Ullah’s point of the need for society to lend credibility, solidarity and help to others in crisis, even when in need themselves.

“I think the most important thing I took away is that peace-builders or activists may stake their claim in different issues, yet by lending their knowledge and passions to other causes, this is what truly creates an international community,” Saltzman said. “I may not know everything about the Rohingya genocide, but by participating in this discussion and lending my understanding of atrocity prevention, I am helping to reshape the narrative and hopefully can generate more awareness.”