New technology developed by a Binghamton University professor and his research partner from the University of Cincinnati could take the blood-testing process out of the lab and put it in a chip.

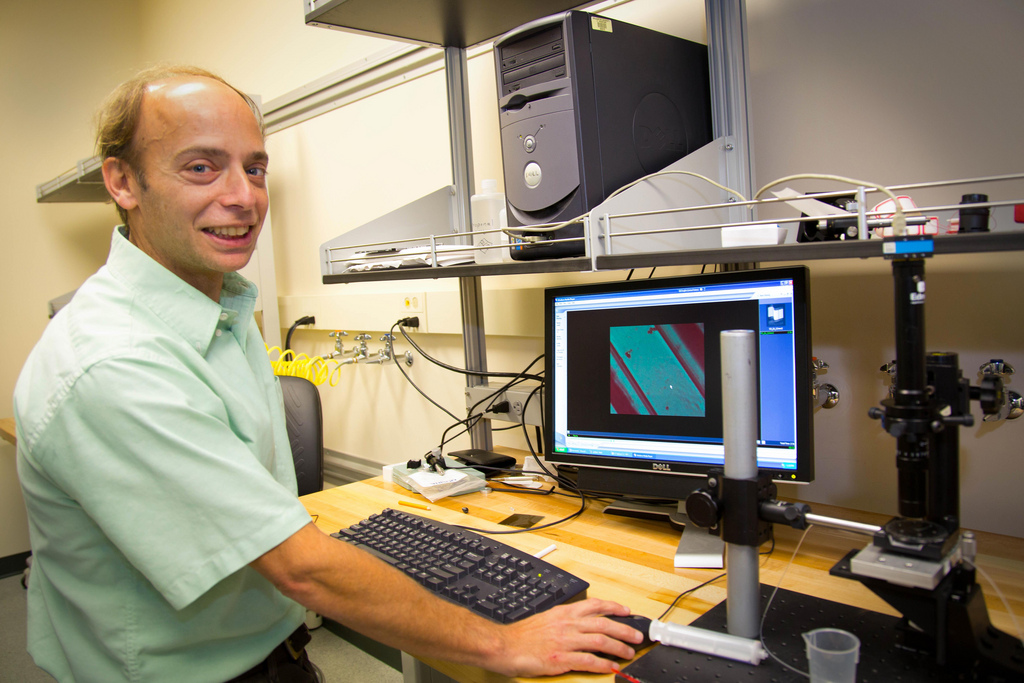

David Klotzkin, an associate professor of electrical engineering at Binghamton, and Ian Papautsky, an associate professor of electrical engineering at the University of Cincinnati, have developed a way of polarizing fluorescent light waves and channeling them through filters to target and illuminate specific particles under a camera to measure their concentrations. It uses white light as opposed to discrete colored light to target cells, allowing the technology to be smaller, cheaper and faster.

This technology, called fluorescence-based monitoring, has a wide application in the medical field, according to Klotzkin.

“There’s a whole field about it called biomems [biological micro-electrical mechanical systems], and it deals with things like making medical test labs the size of a chip, and this is the technology it would fit right into,” Klotzkin said.

The main focus of Klotzkin and Papautsky’s work is to miniaturize and expedite the process of blood testing for viruses in patients, according to Klotzkin.

Klotzkin said fluorescence-based monitoring could save doctors time and money compared to the traditional methods of blood testing.

“The alternative is this giant flow cytometer, which is what we’re trying to replace,” Klotzkin said. “These flow cytometers are on the order of hundreds of thousands of dollars. This prototype is a $400 syringe pump, a $400 camera and a couple of dollars in tubes, so it’s the kind of thing that could be in every doctors’ office.”

Klotzkin works with SFC Fluidics, a company that started working with biomems and fluorescence-based testing within a niche market. He explained that the next step of the process is to develop the technology to the point where it can be put on the market.

“Right now it’s probably better than the commercial stuff, but probably not sufficiently better to justify the switch yet,” Klotzkin said. “I think it needs to reach a critical level where it’s very, very cheap and just compelling.”

Klotzkin said he isn’t sure when the technology will be available in hospitals.

“It’s not ready yet,” Klotzkin said. “It needs to be a lot more controlled and repeatable.”

Klotzkin said he is enthusiastic about the technology’s potential.

“Medical test labs seem sort of primitive,” Klotzkin said. “They have big microscopes and centrifuges and these big bulky things. A lot of it can go into biomems.”

He explained that biomems can be used in other areas besides blood testing.

“You can engineer all sorts of other tests as well, like the devices that sequence DNA and do gene matching,” Klotzkin said. “I think they’re also going to become biomems-based. It just has a tremendous potential.”

Rahul Dixit, a doctoral student studying electro-optics and microfabrication, worked with Klotzkin on his research. He agreed with Klotzkin’s assessment on the future of biomems.

“This technology not only has the potential to be [miniaturized] on a chip level but can be manufactured in bulk quantities which will help in the ‘point of care’ diagnostics,” Dixit wrote in an email.

He said biomems technology can be used to make blood tests accessible at home.

“Measuring your blood sugar with a glucose meter is a very good example,” Dixit wrote. “With the technology we are trying to develop, you can measure various other things like red blood cell count, white blood cell count, oxygen levels etc. with a single ‘prick’ of the finger at your home.”

Dixit expressed his enthusiasm for Klotzkin and Papautsky’s research.

“It just gives me goosebumps just to think about the applications of this technology,” Dixit wrote. “This is not science fiction anymore, this is the world we will be living in 5 years from now.”

Klotzkin encouraged students to look into biomems as a research area.

“If you have a good imagination you could go to a lab, see what they’re doing and see how you could miniaturize it,” Klotzkin said.