After a year of hardship and uncertainty, Calvin Mackie spoke of the importance of never losing hope at his virtual talk hosted by Binghamton University’s Harriet Tubman Center for the Study of Freedom and Equity over Zoom on Wednesday.

Mackie is the managing partner at Channel ZerO Group, chair of the Louisiana Council on the Social Status of Black Boys and Men and president and founder of STEM NOLA, which stands for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) in New Orleans, Louisiana and is a nonprofit community-based STEM program for children. This was the second event of the Tubman Center’s “The 3 Rs: The Road to Reparations and Reconciliation” speaker series. The first event, held last week on April 8, featured Mary Frances Berry, former chair of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, and Hilary Robertson-Hickling, a scholar of the Caribbean diaspora. Mackie’s talk shifted its focus in another direction: the harmful impacts of automation on Black communities and the importance of providing opportunities in STEM to Black youth as a means of reparations and reconciliation.

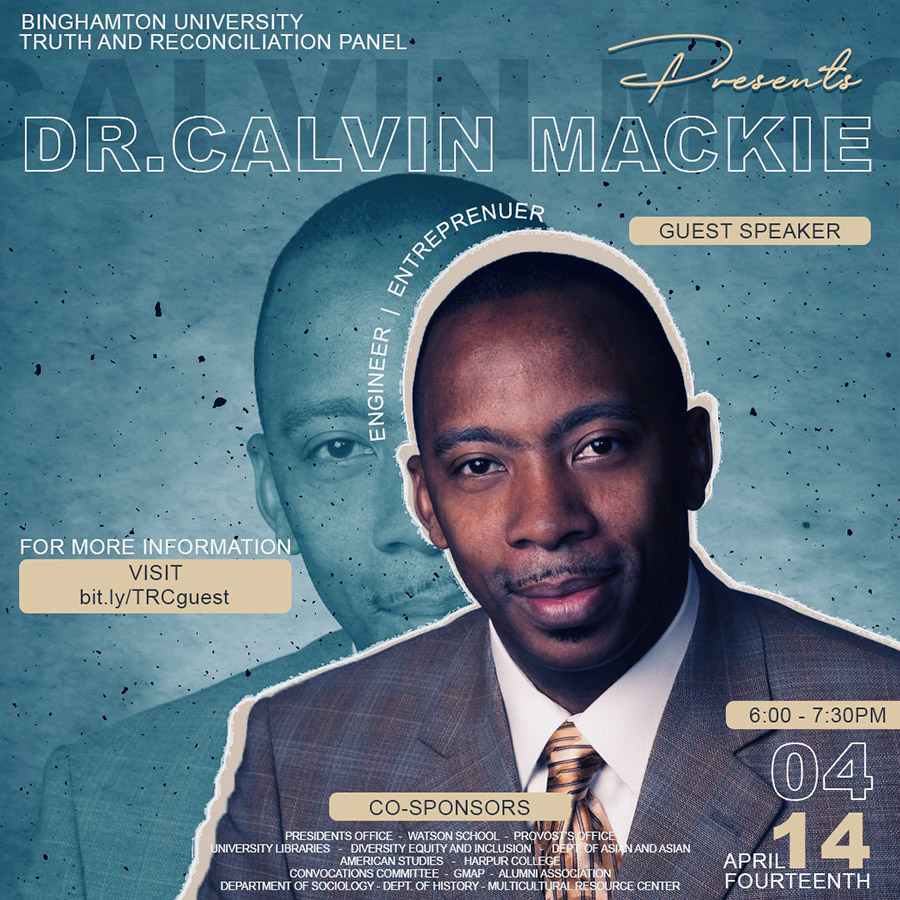

The event was co-sponsored by 13 groups, including the Multicultural Resource Center (MRC), Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) and the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science. Anne Bailey, director of the Tubman Center and a professor of history, said she looked forward to the event and hoped it would demonstrate the importance of conversations about reconciliation in all disciplines.

“We really wanted to make the case that the question of repair in our society has to come from every single angle,” Bailey said. “It is not just something relegated to the social sciences [and] that’s one of the reasons we’re really excited to have him come.”

After introductions from Harvey Stenger, president of BU, and Krishnaswami Srihari, dean of Watson College, Mackie began his talk with a discussion of the importance of having hope in the face of adversity, even though systemic racism and historic roadblocks can make it hard to do so.

“When we think about it, America is built on one thing and one thing only — and that is hope,” Mackie said. “A belief in the system, and if we don’t take care of [it], it is going to crumble right before our eyes.”

Mackie discussed his past experiences, referencing his childhood as well as his professional life. He spoke of being the first of his family to attend college, going from remedial classwork at the beginning of his college career to earning four STEM degrees in 11 years and becoming the first Black tenured professor at Tulane University. Mackie was laid off from the university due to the elimination of its engineering program in 2006 after Hurricane Katrina.

Mackie’s talk described the effects of automation on Black employment going all the way back to the Great Migration in the 20th century. Between the 1940s and the 1970s, Black workers and their families migrated from the South to northern states for manufacturing jobs after the invention of the automatic cotton-picker ceased demand for labor in the cotton industry. According to Mackie, this movement of Black workers occurred right as the need for labor in manufacturing was diminishing with the onset of a “third revolution” of computerization and automation.

“Between 1940 and 1975, many African Americans migrated North, and it was caught between technology,” Mackie said. “It was caught between mass production and electricity, and it was caught between the automation of manufacturing. And why am I talking about this? Because we have seen a 40-year historical decline in employment [in Black communities].”

Mackie also addressed the struggles in racial justice that exist today outside of the employment sector, including the current unrest in Minneapolis, Minnesota following the death of Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old Black man killed by a police officer during a traffic stop on Sunday, April 11.

“I don’t know if they’re rioting in Minneapolis, and I don’t know the next city there’s going to be riots in,” Mackie said. “People are rioting now because of the police state in which we live, and for those of us who have grown up in it, we are not surprised — I’ve never been comfortable with a policeman.”

Toward the end of the talk, Mackie described his newest project — the 42,000-square-foot Innovation Hub for Black Excellence in New Orleans for STEM NOLA. According to The Louisiana Weekly, the project has just received a $1.25 million grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Mackie stressed the importance of providing opportunities in STEM and innovation to young children of color to provide them with the tools and resources they need for success later on in life.

“We need to keep snapping up these centers, so these kids can know that people value them and that they have a place to be what they want to be,” Mackie said. “We know how Black and brown kids and women are underrepresented in STEM … they put a basketball in the hands of every Black and brown kid before the age of 4, but when I say I want to put STEM in their hands, everybody loses their mind.”

Curtis Kendrick, dean of libraries and a member of the Tubman Center’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), said he found Mackie’s talk engaging, optimistic and full of important messages.

“It is a message of hope, one that begs for the optimism to see opportunities when maybe all you’re looking at right now is challenges,” Kendrick wrote in an email. “And then of course the message of resilience was thread throughout his entire talk. That is something people of color need at predominantly white institutions where your very right to take up space may be challenged.”