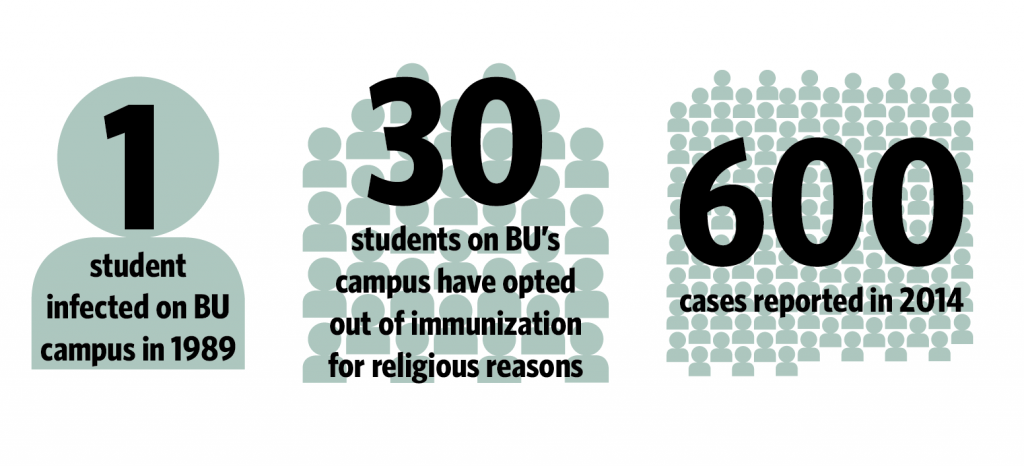

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared measles eradicated in the United States more than a decade ago, more than 600 cases were reported in 2014, leaving many across the country at risk of infection since a recent outbreak in Disneyland. Binghamton University and Broome County health officials, however, say they are prepared to address any local outbreak.

The last reported case of measles in Broome County occurred at BU in 1989. A student was infected, successfully treated off campus and eventually returned safely. According to David Hubeny, the BU director of emergency management, all students, faculty and staff at the time received an additional measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and had to show proof of their updated immunity to enter buildings on campus.

Today, all SUNY students must provide immunization records prior to registration proving they have received two doses of the vaccine. If students cannot provide proof of immunization or are unsure of their status, Decker Student Health Services Center can provide free MMR vaccines.

The initial symptoms of measles, which can appear up to three weeks after infection, resemble cold symptoms, such as a fever, runny nose, cough and red, watery eyes. Three to five days after symptoms appear, the victims develop a rash and their fevers can spike higher than 104 degrees Fahrenheit. The dangers of measles stem from the complications it causes, such as pneumonia and brain swelling.

Although the University requires that students receive the MMR vaccine, not everyone can be vaccinated. Since the vaccine contains the live virus, pregnant women and those with weakened immune systems are advised not to receive the vaccine. Students can also waive immunization for religious reasons. According to Michael Leonard, the medical director of Decker Student Health Services Center, 30 students currently have waived the immunization requirement.

But, according to Leonard, these students are actually protected by the vast majority of people on campus who are vaccinated because of a phenomenon known as herd immunity, which exists when most of a population is immunized against a disease, limiting the chance of outbreak.

However, risk still exists, and Hubeny said there is no simple solution to limiting students’ exposure to measles in the case of an outbreak.

“We could cancel class [if there were a measles outbreak] but we still have a lot of students on campus living in close proximity to each other,” Hubeny said.

Hubeny said that the University is prepared to handle a potential threat by providing protective equipment for staff that would treat infected students, and by working with the Broome County Department of Health to isolate and treat infected students off campus.

The danger of measles stems from its high communicability, or how contagious it is. According to the CDC, the virus can live for up to two hours on surfaces or in spaces where an infected person has coughed or sneezed. An infected person is most contagious four days before and after his or her rash appears.

Because there is no medicine available to treat the measles, the policy of Broome County is to contain the spread of the disease as much as possible, according to Marianne Yourdon, a communicable disease nurse.

“Our main tools are vaccination, isolation of the person that is sick and contact tracing of everyone that would’ve been exposed,” Yourdon said.

Nicholas Conzola, a junior majoring in anthropology, said he was not worried about the disease appearing at BU.

“Because of the necessity of vaccines … no one really thinks about it,” Conzola said. “We take it for granted and don’t realize the devastation that the disease can cause.”