The Old University Union, the Engineering Building, some dormitories and other buildings on campus are caked with a potentially deadly material: asbestos. But Binghamton University officials aren’t worried.

‘Students are never at risk,’ said John Price, BU’s asbestos coordinator.

Asbestos, a mineral-based material, was used as fireproofing and insulation in the campus’s buildings up through the 1980s. People are only at risk when it is disturbed and its fibers are knocked into the air, which may occur during building renovations, for example. Years of exposure ‘ through inhalation of the fibers ‘ can cause diseases like asbestosis (which is similar to emphysema), lung cancer and gastrointestinal cancer. Some diseases are disabling, others are fatal.

To prevent asbestos particles from entering the air, the University follows strict federal and state regulations and has been conducting asbestos removal projects.

‘In addition,’ said Karen Fennie, Physical Facilities spokeswoman, ‘BU goes the extra step and has an asbestos coordinator on staff which provides an additional level of both expertise and monitoring.’

BU is one of the only campuses in the SUNY system that has an asbestos coordinator.

Additionally, the campus’s asbestos is concealed. Either asbestos is meshed in to the matrix of a building material or it is ‘encapsulated,’ said Stephen Endres, training coordinator and industrial hygienist for Binghamton’s Office of Environmental Health and Safety. ‘It’s painted or sprayed over, so basically all the fibers are locked in place.’

Most of the asbestos that remains on campus is in older buildings that were constructed in an era ‘ generally the 1960s ‘ in which the use of asbestos was allowed, Fennie said. The material is still in the Glenn G. Bartle Library, the Fine Arts Building, Dickinson Community, College-in-the-Woods and the East Gym, to name a few.

‘It can be found in areas such as pipe insulation, floor and window caulking or sprayed on steel beams (fire proofing),’ Fennie said.

Binghamton University adheres to standards from the New York State Department of Labor and the Environmental Protection Agency.

‘New York state has one of the most stringent asbestos regulations next to California,’ Endres said.

Regulations require the University to remove asbestos whenever it is to be disturbed by construction or renovation.

If the asbestos is not in danger of being disturbed, then Physical Facilities staff may maintain the area instead of removing the material.

‘As long as it’s not being bothered, it’s no problem,’ Price said.

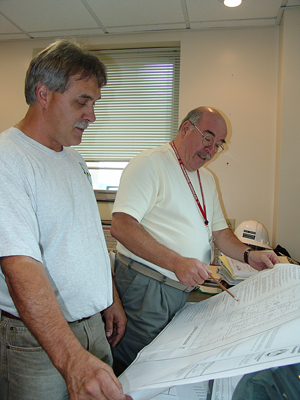

Price and assistant asbestos coordinator Joe Mazzarella oversee the asbestos abatement projects on campus, making sure that the contractors are in total compliance with regulation. Workers take measures like sealing off work sites, showering before putting on their civilian clothes, and conducting air tests before, during and after removal.

Workers removed asbestos from College-in-the Woods’s Onondaga Hall this summer by scraping the ceilings and removing floor tiling, allowing renovation and a fire alarm upgrade. The Engineering Building has been undergoing abatement.

Removal of asbestos from the library began in 1999. Workers gutted, rebuilt and removed asbestos from the fourth and second floors, forcing the University to temporarily relocate up to 200,000 volumes.

‘There are smaller projects, too,’ Fennie said. ‘For example, if a plumber had to replace a valve and it happened to be in an area of a mechanical room where asbestos was used as insulation or in some other way, it would involve a small project to remove it before the repair could be made.’

In situations like these, Mazzarella might take care of the problem instead of hiring a team of contractors.

The University has begun removing asbestos from the roof of the Old Union, but more of the material rests in the bowling alley, ceilings, floor tiles, pipe fittings and fire doors. Asbestos abatement at the Old Union and in CIW will resume after commencement in May 2008.