I had no idea what I would want to be written on my face when I walked into my photography session with Steve Rosenfield on Monday. I thought I would be invulnerable to his “What I Be” project, meant to have its subjects reveal their insecurities, because I’m not a private person. I’m comfortable with my many flaws and I’m usually — thank God — pretty well adjusted.

For five days this week, Rosenfield has set up shop in UUW325 to photograph students for “What I Be.” In 40-minute sessions, he gets students to reveal their deepest insecurities to him and then writes them on their face. Each photo is captioned by a trait about which the subject is insecure. His style isn’t interrogative. He does it a bit like I do my own interviews: asking a somewhat open-ended question and letting the subject speak discursively, before narrowing his line of questioning to arrive at some greater truth.

“What’s the last thing you’d want to tell someone else, because it would make you look bad?” he asked me. I couldn’t come up with anything, so he took a different direction. “So if you have to walk into a room of 25 people, what do you think would be the last thing you would not want to tell them, that might make you feel uncomfortable?” I couldn’t agree with his terms — who were these people? In what context did I know them? Why was I talking to any of them?

“I have a better question,” he said. “You’re sitting in a café, and your girlfriend is sitting across the café … and you have to say something to her that’s gonna not impress her.” Still no dice. “I have a lot of flaws,” I said. “But I’m cool with them.”

So we decided to talk about the flaws that I’m cool with. “I get jealous of people,” I said. Rosenfield asked me how I react. “I get cold towards them,” I said.

I’ve known this about myself for a while. I consider myself ambitious, and when other people are more successful than me — even if we haven’t even been competing — I tend to smolder. For me, success is irrationally a zero-sum game of winner takes all. If I’m not the best person around me, no one can be.

I don’t compete with this attitude, though; it only comes out when I’ve failed at something, or at least succeeded less impressively compared to someone else. It’s not like I sabotage other people or anything. The feeling only comes out when the competition is over.

But it can be harmful. I don’t want to make anyone sincerely uncomfortable, so I withdraw, and turn cold.

I suggested a caption: “I am not only my coldness.”

Although I didn’t know what I was going to have written at the beginning of the session, I knew there was one thing I would be adamant about: correcting Rosenfield’s grammar. Of course I am not my coldness. No one is just one trait and it’s disingenuous to assume that anyone would be defined by a single trait in the first place. “Only” or “just” would serve as a corrective, acknowledging that coldness is a part of me, but also implying that I’m much more than that. Especially if this photo would be an expression of my own identity, which includes grammatical obstinacy.

“It’s a cohesive piece, so that’s why it doesn’t change,” Rosenfield said. But… but… “The part of it that is you — that’s the insecurity part,” he said. “The phrasing of it? That’s my part. The artistic part. So you’re joining my artistic vision with your voice.” Could I have “just” in parenthesis? “Nope.” In a small font with a small arrow indicating where it belongs in the sentence? “’Just’ is not included in the-” I cut him off — could I Photoshop it in later myself? “Nope.”

I went to get a drink of water and left my recorder on the table. He whistled a bit.

“I mean, grammatically, you would use the word ‘just,’ but you don’t have to in a strong statement,” he said when I returned. We will never agree on this.

But anyway, we proceeded to discuss how my coldness manifests itself. I’ll be abrupt: as a way to suppress flaring jealousy. And sometimes I’ll be jealous of people who I don’t know in real life — like writers of really good articles or clever Tweeters — and it won’t manifest much at all, because there’s no person to lash out to. Or, more accurately, to suppress lashing out to.

“Have people called you cold?” he asked me. No, I realized. Few people have. Maybe I’m really good at this — is that scary or good or both?

All good art makes you reconsider the world through or because of the artist’s perspective. Just looking at Steve Rosenfield’s photos did that for me already. To be a part of the process of creating these photos was something else entirely: a self-interrogation that revealed things about myself I had let previously unarticulated.

We had 20 minutes left. We discussed a few other possibilities, but eventually settled on coldness as the subject. I didn’t have any ideas for a pose.

“How do you feel when you’re jealous?” he asked.

I remembered the time I was most jealous of someone — about a year ago — and turned my head and glared.

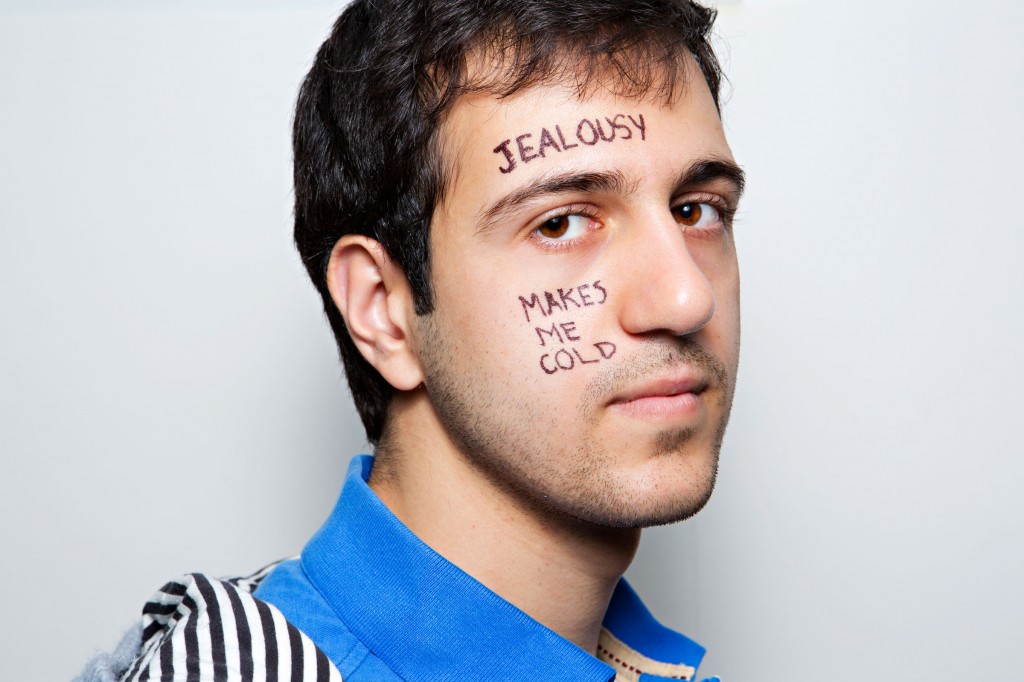

“Jealousy makes me cold,” he wrote on my face. “I am not my abruptness” would be the caption.

“I’m going to laugh a whole lot, so you’re probably going to have to take a few photos,” I warned him as I set myself up by the white poster board he set up as a background. But I didn’t laugh once.