Jordy was born in Cortland, but for the prime of his adult life he’s been at Binghamton University in Science 5.

As a lab rat — specifically, an albino Sprague-Dawley rat, commonly used in scientific experiments — he was bred in a Harlan Lab specifically for research. All of the animals that BU conducts research on are bred in laboratories, said Kimberly Kal-Downs, director of Laboratory Animal Resources.

Jordy was three months old when he came to campus at the beginning of this semester. He lives in a box with his roommate, Timmy, another lab rat of the same strain, in a temperature- and light-controlled room. Usually, he has food (in the form of hard pellets, to wear down the rats’ sharp incisors) and water available to him at all times.

But sometimes, rats don’t have food or water available to them. That happened to Jordy this semester.

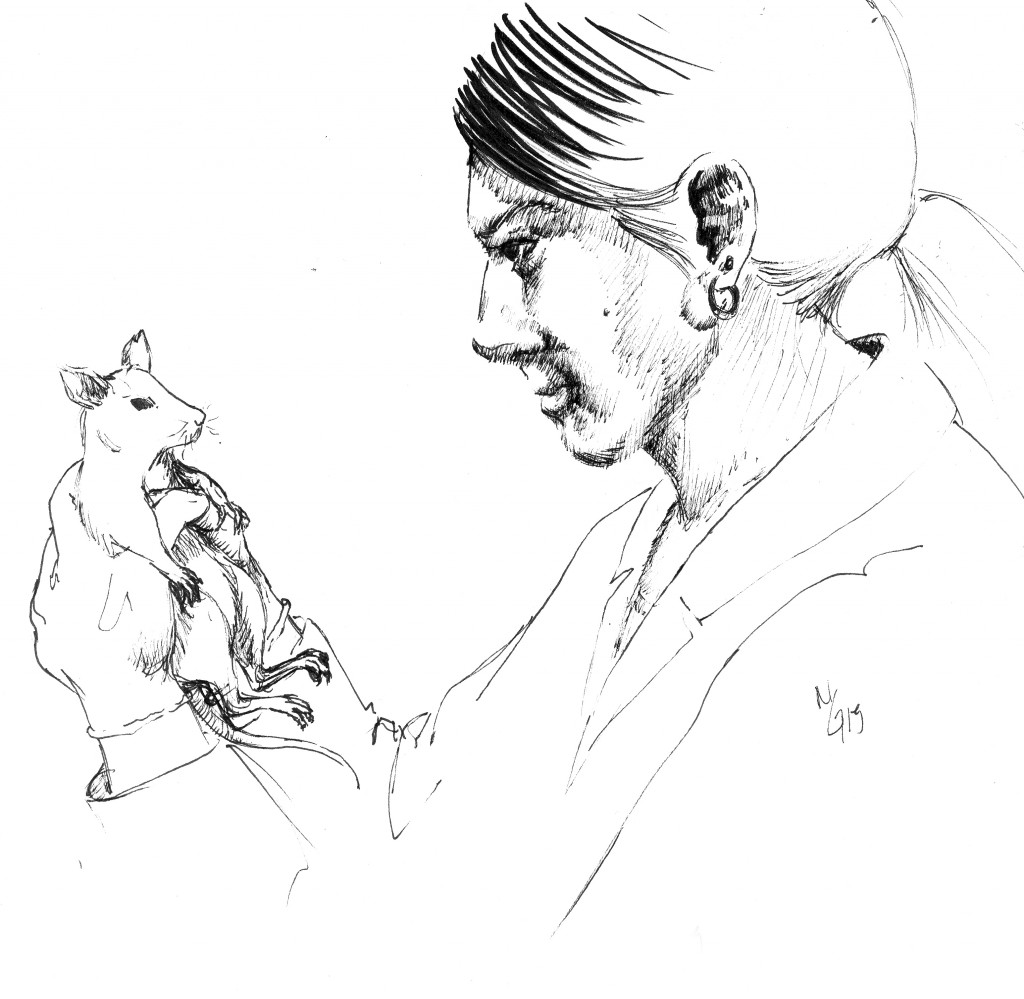

Yedidyah Herskovics, a junior majoring in psychology, experimented on Jordy in his Lab in Learning class. He and his lab partner gave Jordy his name.

“They assigned us a rat, and then I picked him up,” Herskovics said. “And it just so happened to be that he was the best one.”

Jordy, Timmy and the rest of the rats were water-deprived for 23 hours before each experiment, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, so that they could learn to have water as a reward.

“So Mondays and Wednesdays just suck for them,” Herskovics said. “It’s 23 hours without water. That’s the life of a rat.”

The most fun and rewarding experiment — “for me and for the rat” — Herskovics said, was the first one, which was training Jordy to press a lever for water. Herskovics had to train the rat to understand that the lever provided water, even as the lever gave less water the more times it was pulled. The two other experiments were in the same vein, making the rat understand the function of pressing the lever in different contexts, but didn’t provide Herskovics with the same bonding experience as they had that first time.

Science 5 is split in two wings: one side where experiments are conducted in laboratories, and the other side where animal caretakers work. When animals aren’t being experimented on, they spend their time in a holding room, a sort of purgatory at constant temperature and humidity between the two sides.

Jordy was experimented with just twice a week, which meant he spent five full days a week in the holding area, a clear plastic housing around the size of a large shoebox. He spent most of his time playing with Timmy and their toy that was changed every week — Herskovics recalled that one week it was just a wooden cube. Not all of Jordy’s rat peers have names, but all of them are identified individually, usually with marks on their cages or tails. Whether they have names depends on the discretion of their researcher (Herskovics also frequently called Jordy “Ratty”). Herskovics is also unsure about Jordy’s and Timmy’s sexuality, because he never saw them spend time together; another group experimented on Timmy.

Because of his lever-pressing skills, Jordy is used in another experiment now. But unless he escapes, Jordy has two possible destinies. He will either be euthanized and chopped up, and his parts will be analyzed by other researchers. Or he will be euthanized, frozen — so that his corpse doesn’t smell — and then picked up and taken to East Smithfield, Pennsylvania. There, he will be incinerated. Such is the life and death of a research rat.