What does it mean to call a writer “brave”? The word is usually granted to memoirists who write about traumatic experiences and journalists taking on powerful institutions. But there’s another style of brave writing. The Renata Adler style.

Adler’s style of bravery is to approach everything as if it’s no big deal. When Adler reports on events, she doesn’t weigh them down with stuffy rhetoric about history and the importance of every possible outcome. But by doing so, she doesn’t slight or condescend to her subjects; she humanizes them. Her style of bravery isn’t to employ high-flying rhetoric in a salvo against a powerful figure or movement. She writes about all events, no matter how important, equally.

And Adler has certainly written about important events. Consider “Letter From Selma,” her report on Martin Luther King’s march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, originally published in the New Yorker, where Adler wrote regularly from 1962 until the end of the century, and perhaps her most-read work. It’s easy to talk about the march abstractly, simply as a landmark event. Actually being there, Adler observes the pains and fumbles of organizing such a large group of people: “The marchers broke into a chant. ‘What do you want?’ they shouted encouragingly to the blacks at the roadside. The blacks smiled, but they did not give the expected response — ‘Freedom!’ The marchers had to supply that themselves.”

Elsewhere, she notes details that have been forgotten from the usual historical story — like that Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael had to leave in the middle of the march to tend to other events. The small details she observes make the events understandable on a personal level. These people aren’t just witnessing something of great importance, but standing around, waiting a lot and bonding and mingling over a just, united cause.

Renata Adler’s style of bravery is, in other words, understated. And her understatedness did no favors to her reputation. She’s not usually named alongside the other great nonfiction writers of the past half-century, but she certainly belongs in their company.

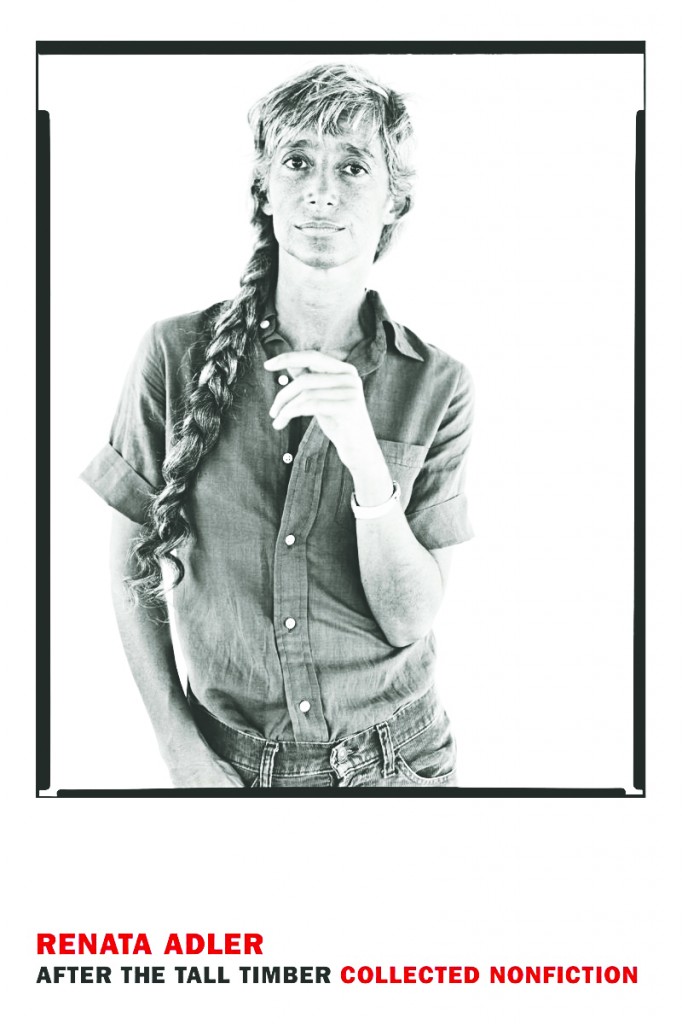

“Letter From Selma” and Adler’s other writing and criticism are collected in “After the Tall Timber: Collected Nonfiction,” just published by The New York Review of Books Classics. The publisher has been working hard to restore Adler’s legacy; two years ago, they republished “Speedboat” and “Pitch Dark” — Adler’s two novels, initially published in 1976 and 1983, respectively, but which had gone out of print — to great acclaim. “After the Tall Timber” draws from previous collections of Adler’s nonfiction writing, “Towards a Radical Middle,” “A Year in the Dark” and “Canaries in the Mineshaft.” NYRB Classics seems to be trying to position Adler’s legacy like Joan Didion’s: as a fiercely independent thinking, a startlingly insightful writer and a female journalist who became well-known despite a male-dominated publishing environment.

The popular mode of reporting when Adler was a rising star was New Journalism, a more narrative, subjective approach to writing that she “particularly detested.” To her, New Journalism may have been lively, but it was fundamentally dishonest. She recalls other writers inventing quotes while claiming to paraphrase sources. Adler’s intelligence and powers of observation always come through in her writing, but she doesn’t write about herself or flaunt a particular style. The introduction of the byline was a turning point in print journalism, she writes; it encouraged journalists to chase celebrity, which “began to overtake and then to undermine the reliability of pieces.”

If journalism is the first draft of history, then Adler’s great idea is that ideas and events don’t make history, people do. Whether she’s reporting from the March from Selma, or the Six Day War, or a national convention of radical political groups, she writes about them not as if they’re political events between nations or ideas, but as if they’re about people. Adler doesn’t expect her readers to hew to a particular political view, like the work Mother Jones or The New Republic normally publishes. But it doesn’t matter. She respects her readers enough to know the basic political and social background behind events, and then plainly writes about the people and events she witnesses.

Adler is known mostly for her writing at the New Yorker, where she spent most of her career, with one exception: her year as a film critic for the New York Times, from 1968 to 1969. Before she was hired, she hardly read any film criticism, but she did her homework, reading several books of criticism before she started working. Her taste, though, came from her experience in journalism. In “On Violence,” she writes that film, like journalism, confers celebrity, even if the subject is criticized. War movies therefore cannot be pacifist, because the agents of violence are celebrated just by being onscreen.

When Adler was at the Times, the Times’ International Desk was banned from Cuba, but the Culture Desk wasn’t. So, at the height of the Cold War, Adler went there and wrote about Cuba’s movie scene. “Cuban art, conscious of the experience of socialist realism in the Soviet Union,” she wrote, “appears relatively free so far of what the Cubans call panfleto, that is, flat propaganda work.” As a cultural reporter, she had a keen eye for observing both the society in which art was made, how much the art itself reflected that society and how the society at large felt about that art. At the time, Cuban cinema was rich on government funds, and audience numbers swelled.

Adler’s film criticism was sometimes casually contrarian, and always defensibly. In her writing, she has a way of not giving a benefit of the doubt to a dominant narrative — usually that so and so director was great, or so and so actor was poor — which is also what made her such a strong reporter. In reporting, her contrarianism is casual because she ignores the dominant narrative of events: She just writes about what she sees. But at the same time, she’s omnipotent; her towers of research bulge beneath the surface of the page. In criticism, her contrarianism is direct, and her knowledge and erudition are readily at hand to dismantle another’s intellectual laziness or incompetence. She often neglected to recognize the achievements of great films, but her harshness was never for its own sake. Any critic could recognize traditional greatness: Only she could see the failures that traditional greatness overlooked.

Adler gave up her post at the Times after a year, but still maintained a reputation as a critic. In 1980, she wrote “The Perils of Pauline,” her most famous essay, a review of Pauline Kael’s film criticism.

The review — on a coworker, no less — was merciless. Kael’s work in the New Yorker was a topic of weekly national conversation. In “After the Tall Timber,” the essay comes with a new author’s note, in which Adler says that she admired Kael’s work until she wrote the review, and then realized it was terrible.

“Now, ‘When the Lights Go Down,’ a collection of her reviews over the past five years, is out;” Adler wrote in the review. “And it is, to my surprise and without Kael- or Simon-like exaggeration, not simply, jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless.” Kael was a writer who started out as a critical thinker, but then became too popular for her own good. As Adler sees it, Kael became more interested in ruling than evaluating, and disliked or liked films for petty or trivial reasons.

In all of her criticism, Adler is a remarkably close reader, picking apart words or sentences to show the weakness of her subject’s arguments. Often, that approach is boring; lingering and nitpicking on these types of details makes readers impatient. Other writers, especially academic ones, who write in this style tend to get so lost in the details that they forget to make their whole point, or their whole point seems unimportant compared to the mass of evidence they’ve relayed. In Adler’s writing, every word not only counts, but is riveting. She has a lawyer’s mind, and writes lucidly about the law, like a Talmudic scholar. Adler has a knack for hanging a writer by their own words. She finds a weak spot in a pattern of argument that seems airtight, and then finds the few sentences that unravels it all.

In “The Perils of Pauline,” Adler writes about the role of a critic itself. “The staff movie critic’s job thus tends to have less in common with the art, or book, or theater critic’s, whose audiences are relatively specialized and discrete, than with the work of the political columnist — writing, that is, of daily events in the public domain, in which almost everyone’s interest is to some degree engaged, and about which everyone seems inclined to have a view.” Adler isn’t just a writer who wrote to a narrow audience, but someone who wrote about events and subjects that concern everyone. She’s an important voice in American letters, and “After the Tall Timber” is a fine tribute to her legacy.