At first glance, a series of shelves showcasing photographs of young people with tea lights in front of them may seem like nothing more than a simple memorial for a tragedy. However, with the fate of those photographed yet unknown, Ambra Polidori’s piece is anything but simple.

The Mexican artist uses postcards to bring to light the disappearance of 43 Mexican students. Polidori’s untitled exhibition is currently on display at the Binghamton University Art Museum.

Gifted by John Tagg, a distinguished professor of art history, the piece is a part of Polidori’s collection, “¡Qué chulo es México!” and is on display in the main gallery. The piece is a collection of 43 photographs on postcards surrounded by tea lights. Those pictured are students who went missing in the city of Iguala in Geurrero, Mexico, after municipal officers opened fire on their bus. The students were on their way to a student protest in Mexico City commemorating the 1968 Student Massacre of Tlatelolco. Only two out of the 43 students who disappeared that day have yet been confirmed dead. The special installation debuted on April 18 and will remain on display until May 20.

Polidori utilizes photographs of the missing students which have been widely employed in mass protests regarding their disappearance and assumed murder. The postcards contain the watermark “¡Qué chulo es México!” or “How Beautiful Mexico Is!” and so with this display, Polidori comments on the ironic use of postcards as a tourist souvenir in Mexico. Other pieces in this collection have been exhibited at festivals in Mexico and abroad, including the National Image Festival and the National Council for Culture and the Arts in Mexico.

In response to this openly political message, Luis Garrido, a first-year graduate student studying sociology, said messages with this gravity are inevitable in any kind of art.

“I don’t think it is possible to separate politics from art,” Garrido said.

Juanita Rodriguez, a guest curator for the installation and a first-year graduate student in history, said she became involved in this project while taking an art history seminar with Tagg.

“It is an unsolved case, and what is worse: no one is accountable yet,” Rodriguez said. “So, that’s why I tried to follow that and symbolize that in these rustic shelves. Although, the tea lights, at the same time that they are grieving, they are also a sort of hope symbol because we don’t know.”

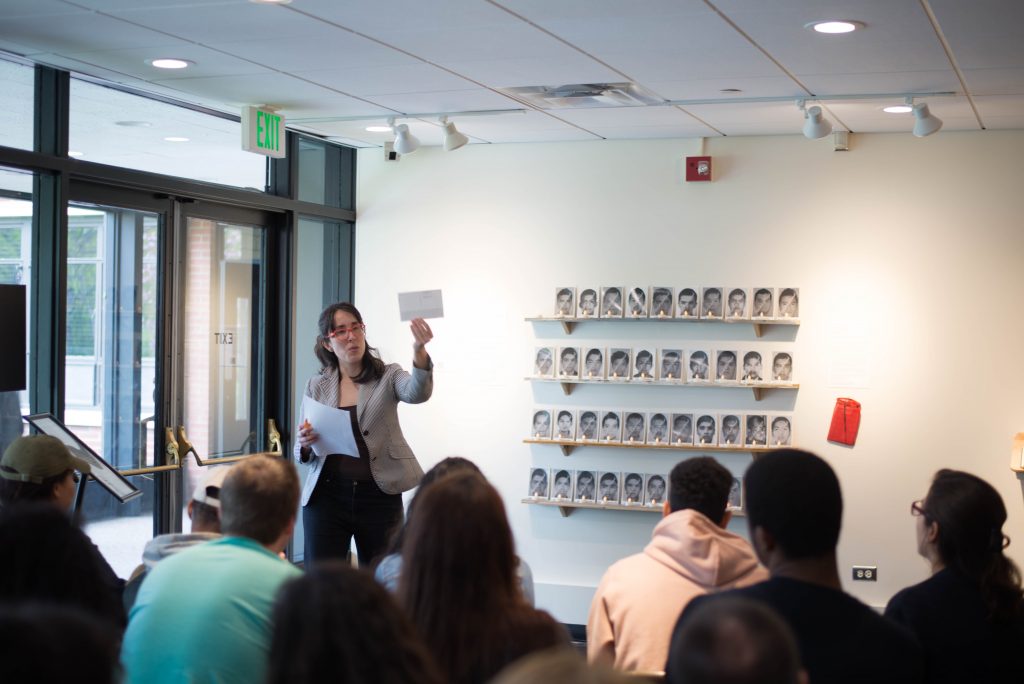

Originally, the piece consisted only of 43 postcards in a mesh bag. In a gallery talk Rodriguez gave on Tuesday, Diane Butler, director of the museum, shared with the audience that paper pieces are usually framed behind glass, but in this installation, the goal was for the art to be accessible to the audience. Thus, she explained, the piece is displayed not “like an artifact,” but rather as a “living piece that people should get involved with.”

In order to enhance involvement with the real issue this piece represents, social media has played a big factor in opening this piece up to the BU community. The BU Art Museum’s Facebook page invites active participation with the work and the debate surrounding it. A post on the page prompts students and others with questions like “If you were to send one of Ambra Polidori’s postcards, what would you write on it and to whom would you send it?” as well as “In what ways can art be an effective vehicle to political mobilization?”

“We want to understand, or at least, we want to make people get involved in the debate behind forced disappearances,” Rodriguez said. “In this moment, our objective is to open up these spaces in which the University community can really speak their minds and one way is using social media.”

The museum’s choice to exhibit a piece with such political significance appealed to undergraduate students like Larissa Flores, a sophomore majoring in biology.

“I think [this piece] is really important and seeing it is really impactful for me because I’m Mexican myself and when this situation happened and I learned about it, it [really hurt] me because it’s happening to my people and my country,” Flores said. “The fact that [those who disappeared] want our country, my homeland, to be better — and this had to happen to them.”