Nothing bad happens to the dog.

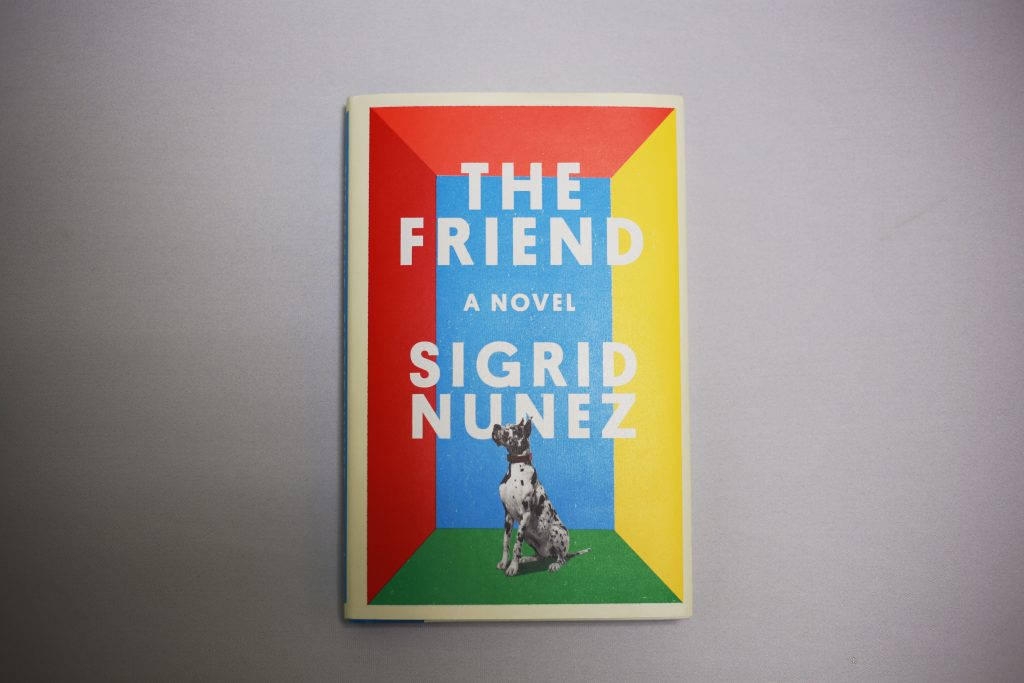

Despite anxieties expressed by the anonymous narrator, the dog is still alive by the end of “The Friend,” Sigrid Nunez’s seventh novel. The book will be released on Feb. 6.

“The Friend” follows the narrator — a writer herself — as she navigates her grief after losing her best friend to suicide. Her friend, unbeknownst to the writer, has left to her his Great Dane, Apollo, and the novel tracks the bond they form over the man they’ve lost. Though the narrator is reluctant to accept Apollo at first, she quickly grows invested in — then fond of — the dog.

Despite Apollo’s centrality in the novel, “The Friend” is as much about the craft of writing as it is about loving a dog. Nunez’s narrator calls on the works of Rainer Maria Rilke, J.R. Ackerley, Flannery O’Connor and dozens of other authors. She quotes these writers and echoes their styles, particularly through Ackerley’s devotion to the dog and Rilke’s transparency about his writing process documented in “Letters to a Young Poet.” The narrator recounts her teaching and volunteering experiences at a writing workshop for trafficked women, and though the novel’s title suggests it directs its focus outward, it is instead a meditation on the perils and pleasures of looking inward, as the narrator takes a microscope to her actions.

Over the course of the novel, we piece together the narrator’s complicated relationship with her dead friend: They met in a class, where he was the teacher and she was the student, and after an unsuccessful tryst, he turned the romance into a friendship. Though he is dead, the friend directs the course of the novel and it appears to be written for him, despite the narrator admitting that she knows he’ll be upset that she’s written it. Apollo both stands in for the friend and replaces him, and the narrator struggles with that shift in the pages of the book.

The book is alternately challenging to read — particularly if you know the singular pain of losing a pet — and touching, as Apollo misses his owner as much as the narrator misses her friend. At one point, when Apollo seems to be particularly low, the narrator starts reading aloud from a manuscript she is working on. When she stops, Apollo barks and nudges her to continue, before falling asleep to the sound of her voice. He, unable to be soothed by music or much else the narrator tries, is placated by a practice so close to his life it seemed inappropriately obvious.

Nunez directs her narrator’s writing to several different targets over the course of the novel, including her friend for most of the book and Apollo during the tear-jerking last chapter. Her writing style flits between memoir and simple observation, and as a result, “The Friend” reads more like a disjointed journal rather than a cohesive novel. Still, this draws the reader into the chaotic tumult of her grief more than a tighter narrative might.

We never learn who the titular “friend” of the novel is — whether it’s the victim of suicide, or Apollo — but by the end, the initial intent is irrelevant. Apollo undeniably becomes the narrator’s best friend and as he enters what looks to be his final year, the narrator fears a second round of grief, perhaps even a deeper one than before. This connection is made ever more clear in the final chapter, when they spend their last summer together at a beach house on Long Island being warmed by the sun.