In our latest installment of “Ask a Professor,” Pipe Dream sat down with faculty members Laurence Elder and Monika Mehta to hear about the albums they’ve had on repeat lately.

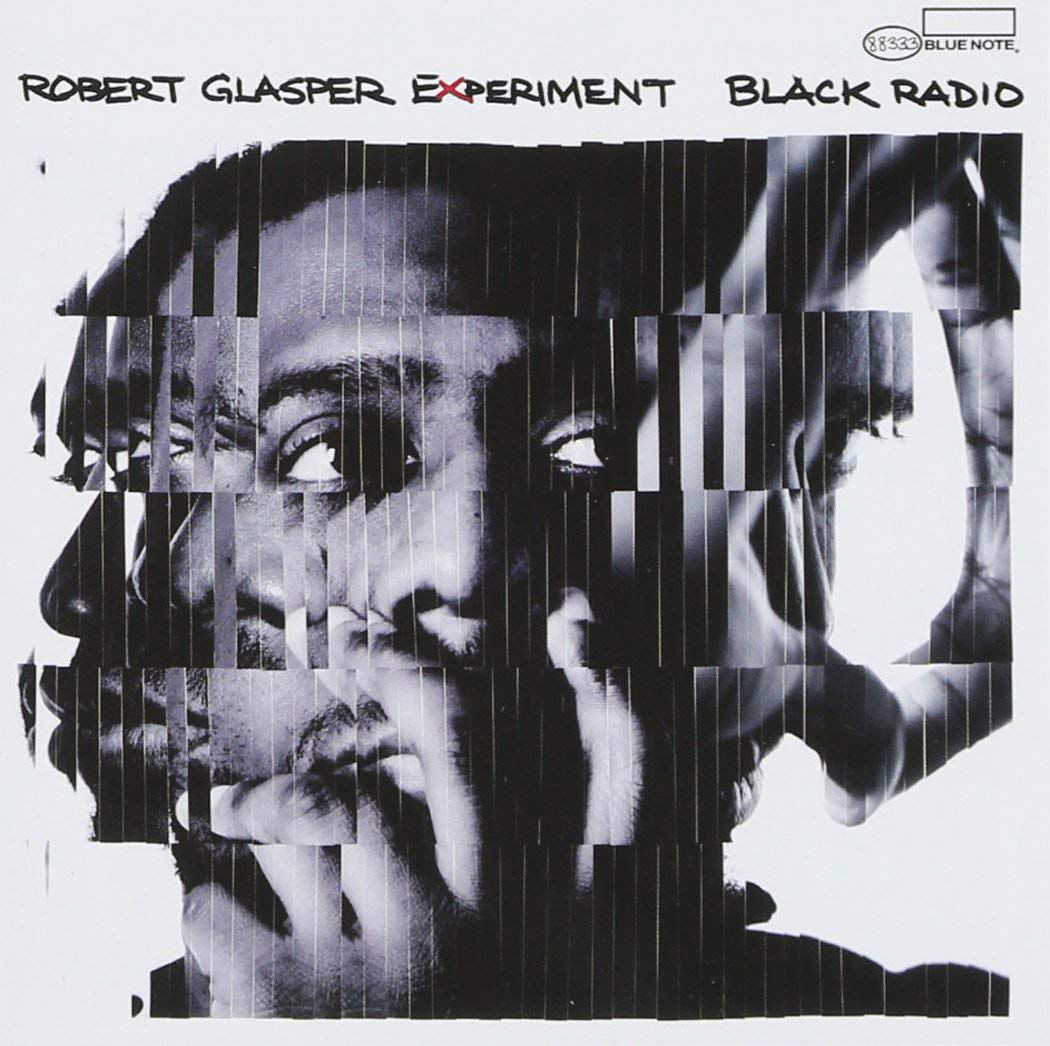

Elder, an adjunct lecturer of music, has recently been revisiting Robert Glasper’s “Black Radio,” released in 2012. Glasper, a 41-year-old pianist and record producer, has released 10 albums since his 2004 debut.

“Glasper is a trained jazz pianist, but his music is really an amalgamation of jazz and hip-hop and soul and funk, put together in packages that are really fresh and current and very original, so there’s something really special about him,” Elder said. “While he draws on the authenticity of the jazz roots, he’s done some things that really brought the music current.”

“When you talk about genres, I think it seems like the walls are coming down more than they used to when putting something into a definition,” he said. “So much music is influenced by jazz now, but it’s not jazz — you wouldn’t put it into the category of mainstream jazz.”

This fall, Elder taught Music 113: Jazz In American Music, which led him to revisit “Black Radio.” Among several other music classes, he also teaches Music 216: Musicianship I and Music 282A: Music Technology, where volunteer musicians come in to be recorded by his students. He said a class he’s teaching can inspire the music he’s listening to. When teaching his class about jazz, he also revisited the work of bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding.

“She writes some really edgy stuff, and did some stuff where she combined jazz with chamber music and some orchestral and symphonic works, so she’s very out of the box and yet still very faithful to tradition,” he said.

He said classes about jazz history are especially interesting to teach because the genre is continually evolving.

“Jazz history, unlike a lot of other types of history, is not done,” he said. “With certain kinds of music history, the books have been closed on it, but jazz is alive and well. The history is unfolding as we speak.”

Mehta, undergraduate director of English and an associate professor of English, usually listens to Hindi film music generated by the Bollywood film industry. Mehta teaches and studies film songs and said while she listens to music for pleasure, she also thinks in terms of where an album falls within the context of the industry and how it compares to other soundtracks.

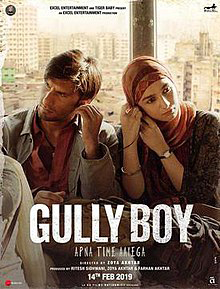

One of Mehta’s favorite albums of the past year is the soundtrack to “Gully Boy,” released in 2019. The film, based on the real-life stories of two rappers, follows a young working-class man in Mumbai who forges his way to rap stardom. Mehta said she’s interested not only in the album’s themes, but in its roster of more than 50 contributors, far more expansive than that of a usual Bollywood film.

Bollywood cinema soundtracks often employ playback singers and have actors lip-sync songs, but the star of “Gully Boy” sings and raps a number of songs on his own. Mehta said her opinion on this creative choice changed after seeing the film instead of just hearing the soundtrack.

“I thought it might have been better if a playback singer had sung it rather than him because he’s not so great, but when I watched the film it made sense that he was the one who did the singing because we follow this guy’s craft from just beginning to rap to becoming a star rapper, and then by the time that happens in the film, the album also changes to give him a voice appropriate for that,” she said. “So for me that becomes interesting — that listening generates one kind of reading about the voice and its appropriateness, whereas watching the film generates a different kind of reading about that same voice.”

Mehta said she was particularly struck by a track that translates as “Distance.” In the film, it’s played during a scene where the main character is working as a driver for a wealthy family, and the young woman he’s driving is crying in the car.

“As the song is playing, the camera moves between shots of him driving the car and her sitting in the back and we see the strip of the car that divides the two of them, and the song itself begins to both narrate and question the class differences that separate them, that also don’t allow them to be emotionally close, that he’s not allowed to hold her or hug her or say ‘What’s wrong?’ because after all, he’s the driver,” Mehta said.

Hindi film music exists outside the context of films as pop music, and Mehta said this aspect of the genre makes it an especially interesting object of study.

“Most people who know the soundtrack don’t necessarily know the film,” she said. “They function both as part of the film, but they circulate outside of it. It definitely makes them very interesting because the song can generate a story that may contradict the story that’s in the film.”