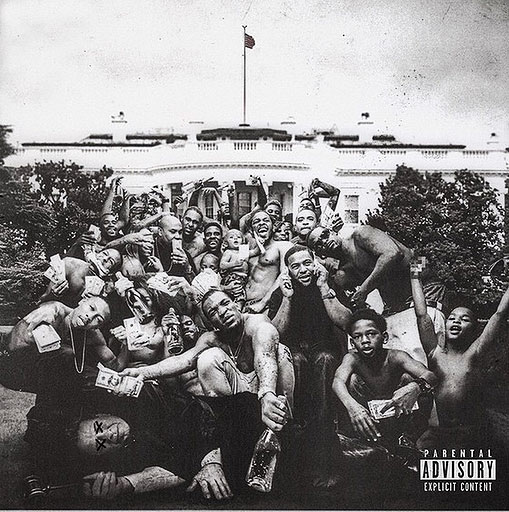

“All my life I want money and power, respect my mind or die from lead shower.” Purposefully sardonic, this line from Kendrick Lamar’s last album embodies the ambitious yet painfully ignorant mentality that much of this nation’s youth have in the face of racial and economic struggle. On his third studio album, “To Pimp a Butterfly,” Lamar channels these familiar themes on a grander scale, sporting an incredible new palate of jazz and funk influence. Conceptually poignant as always, Lamar tackles reinvigorated racial concerns like those most recently publicized in Ferguson, preaching that the only way to break the cycle of violence and exploitation is to emerge from your cocoon as an enlightened butterfly.

After 2012’s “Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City,” to say that there were high expectations for Lamar’s follow-up album is an understatement. “To Pimp a Butterfly” lives up to the hype, though it’s undoubtedly polarizing. Lamar radically expands his sound, while varying the storytelling format of his previous album. Whereas “Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City” is an autobiographical account of his teenage years, “To Pimp a Butterfly” is the story of his people and how fame has forced Lamar to be a role model.

It’s natural to think that a young man at the height of his career would be happy with where he was, thrilled even. But breaking out of the oppressive cocoon of Compton only seemed to create more problems for Lamar. A music career meant leaving people behind. When his friend was shot, Lamar was on tour and could only FaceTime him. Old friends from home pestered him about how he had changed, how he was no longer one of them. As if that wasn’t enough, he found out that his younger sister was pregnant, and Lamar felt like he was selfishly failing those around him. If he was failing those he cared about most, was he also failing the youth who looked up to him? Survivor’s guilt and the onus to enact change are just two of the LP’s major themes.

Lyrics aside, these types of concerns are also expressed in short pieces of dialogue throughout the album. The listener is largely unaware of what they mean at that particular moment; however, each time the dialogue appears, another short line from Lamar has been added to the end. The albums last song, “Mortal Man,” reveals that the dialogue is between him and Tupac, a symbolic moment which sheds light on what it means to be a black youth and the contradiction that is fighting for your rights while promoting nonviolence. The track almost sends shivers down your spine upon first listen. It’s surprising, it’s cathartic, but most of all, it’s empowering.

With a conceptually mature artist like Kendrick Lamar, listening to isolated tracks doesn’t do justice to the greater work. “To Pimp a Butterfly” has a wider breadth than anything he has released up until this point. The songs are decontextualized if not listened to as a cohesive group. That being said, some of the most memorable tracks include “U,” “Alright,” “Hood Politics,” “How Much a Dollar Cost,” “The Blacker the Berry,” and “I.”

In this moment, it’s impossible to say whether or not “To Pimp a Butterfly” will be as beloved as its predecessor, but it certainly tackles institutional racism head-on with staggering word play and conscious activism, summarizing delicate racial issues with tact. Lamar prompts listeners to become a butterfly that betters themselves and those around them, not a “pimped” butterfly that perpetuates ignorance in order to please others. With his third studio release, Lamar retains his crown as king of the West Coast, surprising fans with an unexpected musical shift. At its core, the album is about respecting one another through recognition of each other’s struggle, and it arrives at this conclusion in a way that only Kendrick Lamar could pull off.