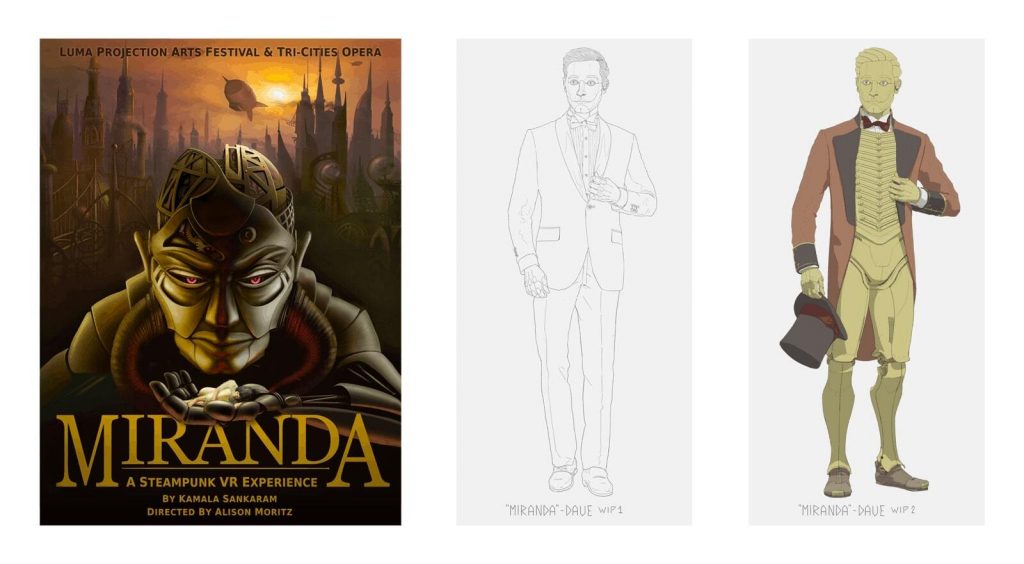

Last Thursday, Sept. 24, the Tri-Cities Opera (TCO) and LUMA Projection Arts Festival premiered their virtual steampunk opera, “Miranda.” After both TCO and LUMA had canceled their season and festival respectively due to COVID-19, they decided to work together in producing a virtual opera. In this opera, the lead character, Miranda, played by Leela Subramaniam, has been murdered and the audience is left to judge who is guilty for the crime. The audience is instructed by an animated robot called D.A.V.E., played by Quinn Bernegger, to go through different scenarios leading up to Miranda’s death. By the end of the opera, the audience virtually selects the character who they believe is guilty. Suspects include Miranda’s mother, Anjana Challapattee Wright, played by Tahanee Aluwihare, her father, Izzy Wright, played by Timothy Stoddard and her fiancé, Cor Prater, played by Trevor Martin.

Though the technology was experimental and imperfect while watching the opera online, the artistry is undeniable and may mark the beginnings of a new genre. The opera was visually appealing and the scenes laid out for the viewer were highly detailed. John Rozzoni, executive director of TCO and executive producer of “Miranda,” described his discussion with LUMA Projection Arts Festival co-founder, Joshua Ludzki.

“When the pandemic hit, [Ludzki] called me up one morning and we were just like, ‘How are we going to take our companies forward when we can’t bring people together?’” Rozzoni said. “His idea for this virtual reality production, a 3D video game platform. He pitched the idea [and] I was like, ‘This is amazing. We’ve got to do it.’ And then we found this wonderful piece.”

Stage director Alison Moritz and composer Kamala Sankaram worked together to cut down the original 75-minute opera into a 20-minute opera.

Sankaram spoke of her inspiration for the opera and how the original opera premiered in 2012 as a live version.

“This piece was inspired by the heyday of reality television and how music can change the way that people were thinking about the characters,” Sankaram said. “Whoever the bad guy on the show has always got the ‘bad guy’ music and it totally changed how the audience [was] supposed to feel about everyone on the show. So I wanted to make a piece that kind of explored that and class inequality because it was really starting to become obvious that that was an issue at the time, and it’s only gotten worse since then.”

Sankaram said she struggled with altering the original opera’s form. In creating an opera for the virtual world, she considered the audience and their ability to remain attentive and involved in the opera while using virtual reality (VR) technology.

“I was excited about it because it was intended to be this sort of sci-fi steampunk thing — which there’s only so much you can do in a theatre, whereas if you have this whole virtual world there are more possibilities,” Sankaram said. “The challenge is that piece is 75 minutes long, and for VR we really shouldn’t go that much past 10 minutes because people get motion [sickness]. So, we had to cut it down quite a bit to make it work.”

Moritz worked with Sankaram on adapting the opera to a virtual setting together. Sankaram conveyed that the timeline of this opera happened more speedily than past productions.

“This was really, really fast … the fact that they basically created a new technology in order to make this work and they did it in three months, which is kind of unheard of,” Sankaram said. “And on top of that, the new version of the opera is so different from the old one that it’s really a new piece.”

Sankaram currently resides in New York City and most of her involvement for the opera was done via Zoom and email. She traveled to Binghamton and was on site the week of the opera.

Anna Warfield, the production director for the opera, shed light on the technology involved in the making of “Miranda.” She spoke of the software and the motion tracking technology which was used.

“The software that’s being used was built by Enhance VR,” Warfield said. “We have three different types of body motion capture happening right now. One is [the] HTC Vive tracking pucks and that’s on D.A.V.E., Miranda is wearing an Xsens suit and then we have a Rokoko [technology] being used by Cor.”

Warfield said that each piece technology has its own set of pros and cons and described an iPhone app which was utilized during production.

“So, it’s three different tracking technologies,” Warfield said. “It’s a bit experimental in that capacity. Then we have Face Cap, which is an app on the iPhone which utilizes depth sensors to track face.”

Warfield said the suit worn by the lead character, Miranda, uses a more profound technology, explaining that the avatars are not aware of the 3D human body. She elaborated on how this can become an issue when a human body is being processed into the virtual world.

“[T]here’s a lot that goes into motion capture and one that we are continually combatting is magnetism and how the sensors are responding to where the body is,” Warfield said. “When magnetic interference happens, it causes the animation to rotate in a way that the body in space is physically not rotating. Her avatar can touch its face, can touch its body, but avatars that don’t know that, ‘This is a pelvis. We can’t cut through it.’”

Ludzki also talked about the significance of their unique three-way partnership to create “Miranda” that included Opera Omaha, an opera company from Nebraska.

“This is a three-way collaboration between these three major players,” Ludzki said. “LUMA and TCO were thrilled to partner with a company that brought so much to the table. Beyond Opera Omaha’s broad geographic reach, the company’s Producing Director Kurt Howard brought an invaluable artistic perspective to the project. It was great to have so many different savvy professionals shepherding the process.”

Warfield also discussed the technical problems. Warfield said there were stand-ins who helped work through the technical glitches while translating characters and moving back and forth between the physical world and VR.

“Two members of the performance were prerecorded characters,” Warfield said. “They were minor characters in the context of the larger piece … to help with the data load that we’re sending out … their animated characters are pre-recorded with fewer data points.”

One scene where Cor and Miranda are virtually in close proximity to one another, but in reality, maintained social distancing with high-tech gear.

“That void scene where you saw Cor and Miranda interacting together in that close proximity … Their play spaces or the platforms in the virtual space are moving beneath them and dictating where they’re going to be … regardless of where the actors [Martin] and [Subramaniam] moved, we were still in control of where their feet were going to be.”