When a student walks into a health care facility, they often have a choice to make — to use health insurance, if they have it, to cover the cost of their care, or to pay out-of-pocket for the appointments, procedures and testing they need.

When it comes to reproductive health and family planning, that choice may be harder. If a student lacks their own health care plan and opts to charge their care to their parent’s or another family member’s health insurance, a document, known as an “explanation of benefits,” is sent to the primary insurance holder. The document explains what the insurance plan was used for and what charges were incurred, meaning a parent could see if their child requested a form of birth control, ordered lab testing for a sexually transmitted disease or infection or had testing or a procedure performed.

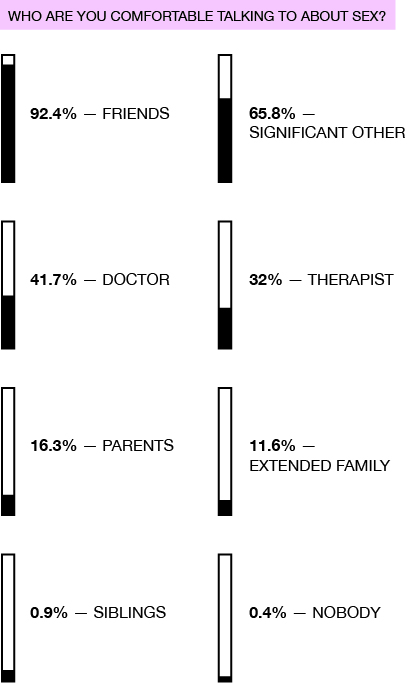

Just 16.3 percent of respondents to Pipe Dream’s sex survey said they would be comfortable speaking with their parents about sex, and less than 12 percent indicated they would talk about sex with extended family members. But for college students, who may live with their parents part time or share health insurance plans or bank accounts, keeping health information private can be difficult.

For some of their health care needs, Binghamton University students can go to the Decker Student Health Services Center. According to Richard Moose, medical director of the center, his office doesn’t participate with or bill any insurance companies, because all of the care they deliver internally is paid for by the student health fee included in the cost of attendance at BU. However, lab work, X-rays and other testing or procedures recommended by staff are outsourced to off-campus facilities, which require payment.

“For example, someone who has symptoms of an STI would need to have a test sent to a lab that can do gonorrhea and chlamydia testing,” Moose wrote in an email. “The off-campus facility will bill the insurance unless the student wants to pay for the test out-of-pocket.”

Paying out-of-pocket means the student would be responsible for the full cost of the testing or procedure they ordered. Often, insurance companies cover some or all of the cost of testing and procedures, lowering the price a student must pay upfront. For STI testing with United Health Services, a regional health care system, students can expect to pay roughly $200.

According to Moose, the center may also notify parents of a student’s medical care if a student is a threat to themselves or others, gave written permission for the information to be shared or the center was subpoenaed by a court to release health information. For students under 18 years old, New York state law allows medical providers to share students’ health information with their parents, but Moose wrote that the center would not do so without consulting the student.

“In general, if a minor student comes to health services for family planning issues and is considered able to understand the risks and benefits of the choices they make, the provider is held to the same standards as [with non-minor students],” Moose wrote.

But if a student needs testing or a procedure and can’t afford to pay out-of-pocket, their only option is to seek reduced-cost care. Family Planning of South Central New York, an affordable reproductive health care provider with a location in Downtown Binghamton, is one of those options. According to Julie Weisberg, director of public communications at Family Planning of South Central New York, students may qualify for free or reduced-cost care under New York’s Family Planning Benefit Program or the provider’s ‘sliding scale’ payment model, which sets fees based on what patients can afford to pay.

“We never turn anyone away for an inability to pay,” Weisberg said. “That means cost is never a barrier to access to care at any of our health centers.”

The Broome County Health Department, located on Front Street in Binghamton, also provides care on a ‘sliding scale’ payment model.

According to Moose, it’s important that students who are seeking reproductive care talk to a provider about their options for protecting their confidentiality.

“I think the take-home message is that we don’t want to share information without the student’s permission,” Moose wrote.