November is National Native American Heritage Month, a period of time dedicated to learning about the history of Native Americans in every location of the Americas. With 12 Indigenous reservations on its land, New York is no exception to learning about local Indigenous tribes and their rich presence.

The Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee, have resided in what is now called New York state for over 4,000 years and consist of six nations: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora. There are also a number of different Algonquin tribes in the state. Despite popular belief, these tribes are not extinct, according to Alyssa Mt. Pleasant, assistant professor of transnational studies with a specialization in Haudenosaunee history and studies at the University at Buffalo, and a Tuscarora descendent.

“One of the things that I would emphasize in a discussion about Haudenosaunee people in what is currently New York state is that there are vibrant Indigenous communities on reservations and also in urban areas throughout the state,” Mt. Pleasant said.

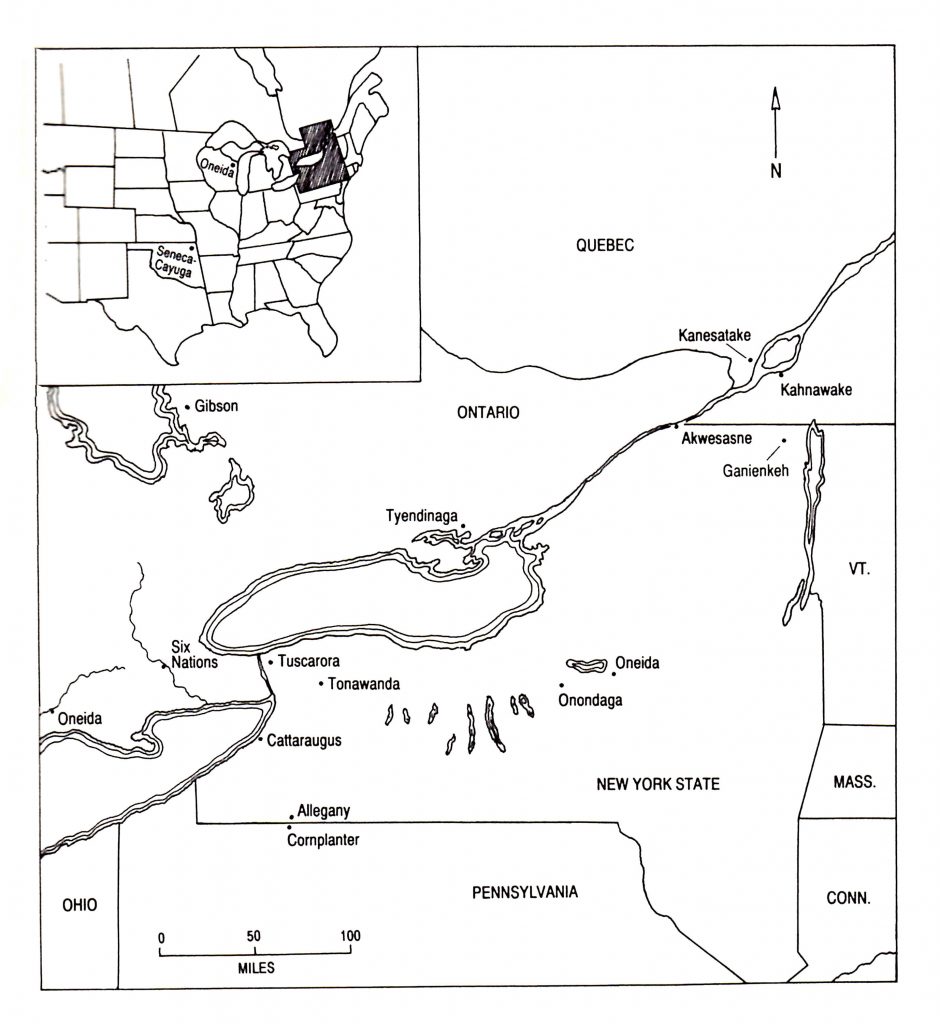

The Onondaga reservation is the closest reservation to Binghamton, New York. According to a map provided by John Fadden, a founder of the Six Nations Indian Museum, the others in New York are Allegany, Cattaraugus, Oneida, Tonawanda, Tuscarora, Akwesasne, Ganienkeh and two other Algonquin communities in Long Island, Poospatuck and Shinnecock. Mt. Pleasant says that many Indigenous folk live in places scattered throughout the United States.

“Native peoples are your neighbors, your classmates, your colleagues and co-workers, and that is something that not enough people recognize,” Mt. Pleasant said. “It’s something that, as somebody who teaches undergraduates, I often have found that I have to do a lot of work pushing back against dominant narratives of Indigenous disappearance.”

Brenda LaForme, 64, a cultural interpreter and education program coordinator for the Iroquois Indian Museum and a member of the Onondaga Nation’s Beaver Clan, agrees with Mt. Pleasant. LaForme, whose Haudenosaunee name is Odasiyo, was born in the Six Nations Indian Reservation in Canada and attends traditional longhouse ceremonies and speaks the language of her ancestors.

“I’m still here today,” LaForme said. “Many of our Haudenosaunee people practice their culture, they practice their tradition, but many also don’t. A lot of the Haudenosaunee people are Christianized now. I’m not. My family’s not and a lot of Haudenosaunee people are not Christian — they go and attend ceremonies in their longhouse.”

LaForme emphasized that she is present, despite history’s attempt at erasing that existence.

“I go to Walmart,” LaForme said. “Sometimes I even stop at McDonald’s. We live today and we still dress like you, but we still practice our ceremonies. There’s 19 of them throughout the year held in the longhouse.”

LaForme spoke of the injustices she has witnessed, experienced and heard from her own peoples.

“My mother is a survivor of residential school,” LaForme said. “Canada and the United States took children away from their parents to take the Indian out of the child, they said. We were beaten for speaking our language. We couldn’t pray the way we pray, we couldn’t practice.”

LaForme said churches played a large part in Christianizing Native Americans to become “homogenized white-milk, white people.” LaForme also noted that the United States and Canada have disregarded many treaties by continuing to oppress Native Americans.

“They [Haudenosaunee peoples] converted to survive,” LaForme said. “How do you get a nation and churches to acknowledge that? What do you say? ‘I’m sorry?’ What does that mean? ‘I’m sorry,’ when there’s no justice done, when your curriculum hasn’t changed, when churches don’t.”

According to Mt. Pleasant, many incorrect narratives are largely due to the shortcomings of the New York state curriculum for elementary, high school and higher education, in some cases. In a study by Pennsylvania State University researchers, most of the curriculum American K-12 students learn about Native Americans concern periods prior to the 1900s. The study found that standard narratives, such as “Thanksgiving, Columbus Day, the French and Indian War, the War of 1812 and general standards related to colonial and early American settler conflicts with Indigenous peoples dominated the standards across all grade levels.” These narratives are ones that tend to not be inclusive of Indigenous peoples and their real past and present experiences.

LaForme said that the reason why Native Americans are treated as past relics is that European people do not want to face the shame of what they have done to Native Americans. LaForme also noted that the educational curriculum does not do justice to the true history and their present-day existence.

“Even if you look at your curriculum, they don’t start teaching Native American until October, just around Thanksgiving time, November right, in your school curriculum at fourth grade and we teach them, right from the beginning, that we live in the past,” LaForme said. “Fourth grade, fifth grade, sixth grade, but up to high school they’re learning about us living in the past like antiques or something. We still live today.”

Mt. Pleasant said that many undergraduate students are interested in learning more about the Indigenous community, but often ask questions that limit the versatile and vibrant nature of Native Americans.

“One of the things that I try to emphasize in some conversations is that your ignorance is a reflection of systemic racism and settler-colonial agendas that are intended to erase Indigenous peoples and eliminate tribal nations,” Mt. Pleasant said.

Despite this, individuals can still learn about the Indigenous community surrounding them. Fadden noted that people interested in learning more can find all sorts of avenues to do so and hopes the education system will change to allow for more of that.

“Read books on the topic, visit museums and other forms of education,” Fadden wrote. “It would also be nice if the educational systems played a more [effective] role in this effort.”

Mt. Pleasant suggested students go to certain sites to learn more about Indigenous communities from undigenous peoples. Illuminatives.org is a nonprofit led by Native peoples with an aim to “increase the visibility of — and challenge the negative narrative about — Native Nations and peoples in American society.”

Mt. Pleasant also suggested visiting the Ganondagan State Historic Site, the original location of a Seneca town of the 17th century, located near Rochester, NY. It is the only historic landmark in New York state devoted to Native American culture, art, history and more. There are virtual events and exhibits open for public view which feature artwork from Haudenosaunee artists. Additionally, there are a number of volunteer and educational outreach programs possible via Zoom or Skype. Visit the site online here: https://ganondagan.org

One of the most important sources of narratives people can consume come from the media, noting that journalists should be aware of how to frame questions and Indigenous topics. To do so, she suggested using the Native American Journalists Association’s media guide which “encourages reporters and editors to learn about the complexities of Indigenous nations and their varied communities.”

Lastly, one of the simplest actions individuals can take to expand their knowledge and reduce their ignorance toward Indigenous communities is to follow Native American people on social media.

“One of the things that you can do is actually is to start following Native people on Twitter or other social media,” Mt. Pleasant said. “I think Twitter, in particular, there are some great, some amazing Native activists and scholars and public intellectuals who are circulating reliable information and ideas.”

LaForme said that those interested in knowing more should honor Indigenous peoples and learn what schools don’t teach them.

“Don’t learn what [they] teach, what they want you to learn, what they want you to know,” LaForme said. “Learn what they don’t want you to know of what they’ve done. You can’t escape it, you can’t. There’s nothing that they can do either to change or fix it. That’s what their ancestors did and also, they’ll say [to us] ‘Just get over it.’ What do you mean? How do you get over it?”

To keep the history of the Haudenosaunee, LaForme said, is also a duty that she carries with her every day. Despite not being able to speak fluently in her language because her mother was beaten for speaking it, her own reservation is going through a revitalization of the language to be learned by future generations. Moreover, traditions and ceremonies conducted in the longhouse are continuously practiced and passed on. LaForme has five children and, as a person who has lived over six decades, has seen no change from the government in acknowledgment or accommodations to her peoples.

“I can also speak from the Haudenosaunee,” LaForme said. “We have to keep pressing forward and transferring what we do know to our children or eventually, we will be extinct.”