About 40 seconds into the Grateful Dead’s now legendary live recording at Binghamton University, a voice asks, “How come things are so strange around here?”

At the time, it was a question not easily answered. By May 2, 1970, hippie culture had reached its apex at the school, and with it came acid trips and a new ambulance corps, campus conflict and canceled classes, tragedy and transcendent guitar solos.

As the coronavirus pandemic causes paralleled upheavals in campus life, the story of May 1970 is worth retelling 50 years later within the context of BU’s ever-changing political landscape. It starts with Jerry Garcia and company in the West Gym.

The music

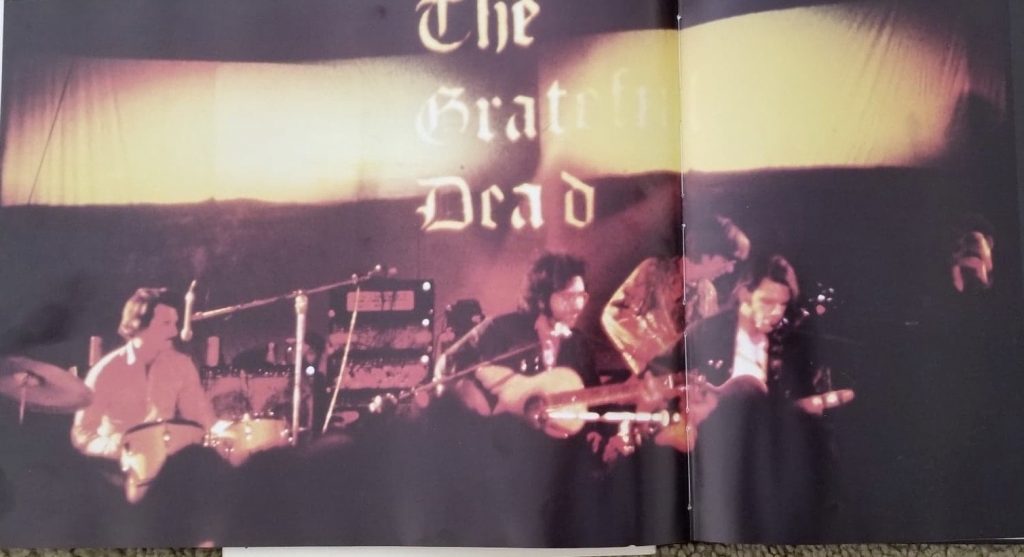

On a Saturday evening, members of the Tau Alpha Upsilon fraternity shepherded a crowd of BU students, students from neighboring colleges and traveling “Deadheads” into a newly built gymnasium. Soon after, the Grateful Dead would commence their nearly three-hourlong set.

Richard Wolinsky, ‘71, said the Grateful Dead had not yet reached legendary status at the time of the concert, which took place barely a year after the band played at Woodstock in Bethel, New York.

“At the time they were just another one of the West Coast bands, albeit one with an amazing reputation, but I don’t think in 1970 they had the kind of reputation that they gained years later,” Wolinksy said. “It was only later that they became ‘The Dead’ in that sense.”

The Spring Fling of the late ‘60s, or “Spring Weekend,” usually featured a popular artist, whereas other concerts throughout the year were smaller. In 1970, BU’s campus had already seen visits from folk icon Arlo Guthrie, classic rock staple The Band and gospel singer Marion Williams.

According to Wolinsky, Harpur College students of the period listened to records, but radio was also a huge source of discovery, especially since college radio provided an alternative to mainstream stations. The acid rock genre, pioneered by bands like the Grateful Dead, was just one facet of a diverse musical landscape.

“I was kind of always between the hippie crowd and the student government crowd, but the student government crowd was listening to a lot of Phil Ochs or Bob Dylan or Simon & Garfunkel,” he said. “You had different groups with different tastes.”

Students at the time might have owned one of the band’s two studio albums, but they also might have heard about live shows through word of mouth. Wolinsky said the band’s live shows conveyed an entirely different image from the one crafted by its record label, as was the case with other captivating live acts like Janis Joplin.

“You’d hear of these groups, but since the albums did not necessarily reflect who they were, you didn’t know what they sounded like unless you went to a concert,” he said.

At the BU show, the band debuted the New Riders of the Purple Sage, an opening act that shared members with the Grateful Dead, while trying out a new act that split their shows into an acoustic and an electric set. Wolinsky’s review of the show, printed in BU’s Colonial News and stylized to sound like it was written on acid, maps out some highlights: “Viola Lee Blues with three buildups,” “a stirring rendition of Good Lovin” and a “totally controlled and superb Morning Dew.”

Of the more than 2,300 concerts the band has played since its formation in 1965, the BU show is consistently ranked as one of its best, with Rolling Stone’s David Fricke ranking it in his top 20 live Grateful Dead performances and Grateful Dead archivist David Lemieux ranking it in his top five. The show was recorded by then-producer Bob Matthews and released in 1997 as “Dick’s Picks Vol. 8,” now coveted among collectors for whom live tapes are as integral to the band’s canon, if not more so, than studio albums. Wolinsky’s review was included in the liner notes of the physical release. Many of the band’s live tapes were recorded and circulated by concertgoers, and Wolinsky said this tradition marks the Grateful Dead as a “people’s band.”

“Most bands did not allow people to tape, and the Dead encouraged it,” Wolinsky said. “There was a certain freedom with the Grateful Dead that other bands did not have, and a lot of people thought they were crazy for doing it, but it turned out to be the smartest move they ever made.”

While the Grateful Dead didn’t always put on great shows — their Woodstock set was famously sloppy — Wolinsky said the members’ chemistry and musical ability allowed them to soar on the day of the BU concert.

“I think part of it was they were primarily an instrumental band, so even though they sang, and they could sing well, they were basically a jazz band who played rock and roll, or jazz or just spaced-out stuff,” he said. “I think their ability to improvise, to go off in whatever directions they could and have the other members of the band keep up with them, was fairly unique, and I think that’s how their audience grew.”

More than anything else, he said the concert was a miracle of chance, a product of the right band in the right place at the right time.

“It’s a venue, it’s an audience, it’s the way the musicians were feeling on a particular night,” he said. “If you’re in a place where the confluence of all that comes together, you’re gonna be seeing something very special.”

The drugs

The Grateful Dead’s legacy has become associated with not only epic live shows, but with LSD. Sound engineer Owsley Stanley maintained his status as a counterculture legend by keeping concertgoers and festivalgoers fueled on acid, and the drug was certainly common at BU during the apex of the hippie era.

According to Sal Caruana, ‘73, tripping students were sprawled on couches in the Student Center or in residential hall lounges daily, and while BU had a first-rate infirmary, the only drug counseling on campus was a student-run program called High Hopes, which was run out of a small room and contained three cots, some anti-drug literature and one student volunteer on duty 24/7.

Caruana said campus drug use reached its peak at the concert.

“Between the two sets there was an intermission, and in the intermission, a lot of people went outside, and it was pouring and these people were impervious to the rain, and that told you that they were really into the music or really out of their skulls,” Caruana said. “The whole Deadhead phenomenon was also very connected to drug use and that piece of it we weren’t prepared for. No one said, ‘What are we gonna do about that aspect?’”

When the West Gym finally emptied around 1:30 a.m., there were eight individuals left lying on the floor in various drug-induced states. Student concert staffers rushed to call local hospitals for ambulances. Campus security was also called for help, but EMT training was not yet part of their skill set.

Tensions between a conservative, working-class Binghamton community and the student body had escalated since the first student political marches Downtown in the late ‘60s, and according to Caruana, this mutual distrust influenced how student staffers handled the post-concert emergency.

“The conversations with hospital dispatchers were troubling, and the indifference our callers were sensing was thought by some to be ‘hippie payback,’” he wrote in an article on the founding of Harpur’s Ferry. “(Today, decades later and in fairness to those dispatchers, our perceptions could easily have been blurred by the agitation and impatience that commonly besets those who call for emergency assistance.)”

In an effort to avoid more “hippie payback,” Caruana and others filled a few cars with the unconscious concertgoers and rushed them to three separate hospitals: United Health Services (UHS) Binghamton General Hospital, Lourdes Hospital and Wilson Memorial Hospital, where they were promptly accepted and treated. According to Caruana, none of the eight individuals had been recognized as BU students, and the University never confirmed news of their outcomes.

“The administration’s policy toward the obvious was ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’” Caruana wrote. “It sounds so incredible today, but back then benign neglect was the way it was managed on most college campuses when it came to hard drugs.”

The incident inspired the establishment of Harpur’s Ferry, spearheaded by High Hopes founder Adam Bernstein, ‘73, and Jon-Marc Weston, ‘73, of Tau Alpha Upsilon, which emptied its treasury into the project. In the wake of the concert, premed students and fraternity brothers alike banded together to get the volunteer ambulance program off the ground.

The movement

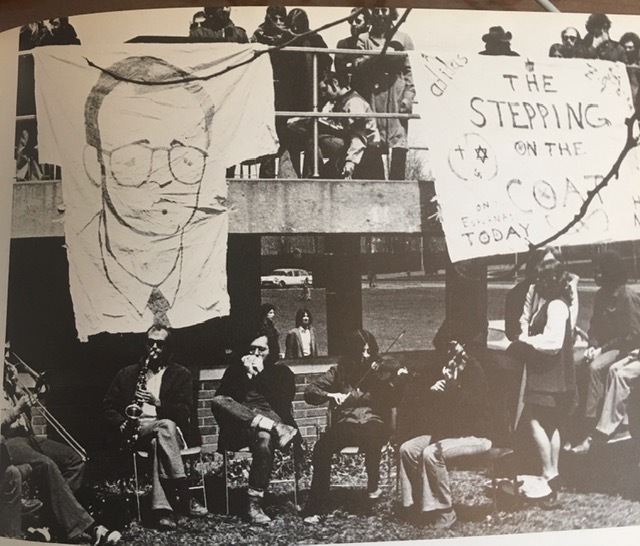

May 1970 didn’t just landmark BU’s music and drug cultures; it saw an unmatched period of student activism.

BU, previously called Harpur College before its name change in 1965, was a small liberal arts school with a national reputation, and as its intellectual communities bloomed, so did direct action on campus. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, it was as common to see a “guerrilla theatre” performance in the cafeteria as it was to see a protest on the Peace Quad.

Students today can look to previous generations of Binghamton University students for hope and inspiration in dealing with difficult times.

“Activism was happening in highly developed liberal arts schools, so places like University of Chicago, University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Ivy League schools, and we had students who were academically eligible for these places, but financially couldn’t make it,” Caruana said. “The whole liberal arts tradition [at BU] was an accelerant.”

Young men of the period anxiously threw themselves into their studies in efforts to avoid the draft via admittance into graduate school, a loophole that was later closed. All the while, protests Downtown, on Vestal Parkway and at the University president’s office, often in response to military actions and the presence of Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) on campus, gained traction. When Nelson Rockefeller visited BU a few years later, backlash from students resulted in an unforgettable image of him flipping off his audience.

On April 30, 1970, two days before the Grateful Dead concert, the Nixon administration announced it was invading Cambodia in pursuit of its Vietnam objectives. Two days later, campuses across the nation reacted to the shooting of four Kent State University student protesters at the hands of the National Guard, and on May 15, two students were killed when police opened fire on a dormitory at the historically black Jackson State College. In the week following the concert, BU students and the Faculty Senate voted to strike, and finals were made optional as classes were suspended.

“It’s an important moment to celebrate the significance of college activism because when that happened, the protests were spontaneous and when you look back at the numbers, I’d say two-thirds of the colleges had to close because students said, ‘college isn’t important anymore, this is important,’” Caruana said. “‘What happened to these kids is important, a president that lies is important.’ It was a mass walkout from college, and that’s historically important because there’s been nothing like it since.”

While not every BU faculty member supported the anti-war effort, there were several who led protests and demonstrations alongside students, including University President G. Bruce Dearing.

Stephen McKiernan, ‘70, remembers students being warned by professors not to wear their BU jackets Downtown as local distaste for the protests escalated.

“A lot of people in Binghamton supported the war, and even when I used to take the bus back and forth into the city, students would go in pairs,” McKiernan said. “There were a lot of people who didn’t like Harpur [College] students.”

In the Colonial News’ last issue of the semester, the student paper’s Editorial Board wrote about an open forum that occurred between students, faculty and silent majority demonstrators.

“The demonstrators came here thinking Harpur [College] was closed,” the article reads. “They believed that they were taxpayers, paying for an education which we were not getting … We tried to convince them that we had gotten more of an education in the last two weeks than ever before.”

Momentum continued through graduation, where peace sign buttons were passed around and pinned to caps and gowns. McKiernan still has his.

“The whole spirit of the ‘60s and the whole spirit of Kent State was at that graduation,” he said.

A former history major, McKiernan has amassed a large collection of ‘60s memorabilia since his days at BU, much of which he donated to a 201y Glenn G. Bartle Library exhibition. While he missed the Grateful Dead concert due to a broken arm, he’s seen the band on three other occasions. He favors the BU record above all others in his collection, crediting its singularity to the pivotal time of the performance.

“If the Grateful Dead had come a year before, it would’ve just been another great concert for the Grateful Dead, but they knew what was going on around the country, and they were empathizing and they were doing it through their music as they always did,” McKiernan said. “There was a tension in the room, there was a tension in America and they were also affected by what was happening.”

Since 1970, BU has changed in enrollment numbers and diversity of course offerings, expansions that have eroded its identity as “the Berkeley of the East Coast,” according to McKiernan.

However, McKiernan said there’s still power in a small, dedicated fragment of the student body, and while popular portrayals of the hippie era paint activism as the norm, vehement opposition to the war was not as universal as some might think.

“Of the 74 million boomers, it’s estimated that only 7 percent of them were ever activists,” he said. “Now that’s a small number, but add up the millions of 7 percent of 74 and that’s quite a big group. The bottom line is everything starts small and then builds up, and there’s no question that students played a major role in ending the Vietnam War.”

While he recognizes that today’s students are often juggling more than they would have been in 1970, McKiernan said the events of that May can serve as a model for campus activism 50 years later, emphasizing that political action indicates an intellectually engaged campus.

“When students are activists and they’re responding to something in one way or another, it shows that the campus is alive, it shows that it’s active, and I know it can create tensions, but it is important because it’s a microcosm of our society,” he said. “If you have even a small inkling of activism on a college campus, then you have a healthy campus.”